Nurturing the Potential of Your People

"If the outcome is good, what's the difference between motives that sound good

and good sound motives?"

Laurence J. Peter, Author of The Peter Principle.

Effective managers are able to recognise the potential of their staff, to nurture that potential, to motivate the employees so that they may achieve more, but to be able to identify the limits of their potential

There is a paradox inherent in that paragraph. Potential, by its very definition, is incapable of being limited; it is infinite. But this is to equivocate; it is the difference between the ideal and the practical. In the "real" world, there are too many undisclosed agendas in a person's apparent inability to mature and develop. Too often people in the workplace have an investment in holding themselves back; there may be other demands on their time and their energies, other needs they wish to satisfy, that are more important than promotion.

A mark of the manager's skill is to be able to identify which staff will respond to motivation and which staff will, in Peter's prescription: "be promoted beyond their capacity for competence".[2]

So the managerial skill is not merely the recognition of potential in those people who will benefit from careful nurturing, but also to identify the personal motivating forces that may be most effectively harnessed in each individual for optimum result. Heller and Hindle [3] make the very useful point that motivation is equally necessary on other levels. It is not enough to encourage only subordinates to expand the frontiers of their potential, but colleagues and senior personnel also will benefit from being asked to share your vision, your ideas, and your enthusiasm.

|

To release the full potential of employees, organisations are rapidly moving away from "command and control" and towards "advise and consent" as ways of motivating. This change of attitude began when employers recognised that rewarding good work is more effective than threatening punitive measures for bad work [3] |

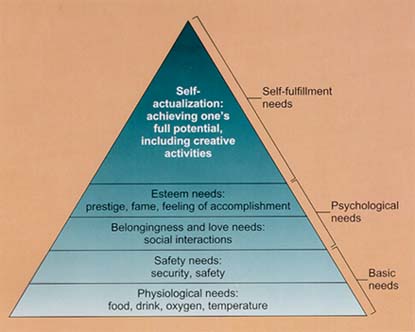

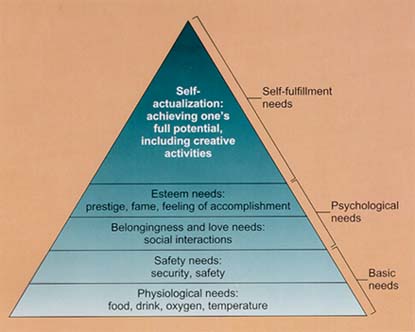

An excellent tool for assessing the values and belief systems of your employees, and using that knowledge in order to motivate them to achieve more of their potential, is Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. [This model was described in Nurturing Potential's Issue No. 4 - http://www.nurturingpotential.net/Leader3.htm - Ed.]. This recognises that people's needs follow a very specific and clearly defined order of importance: until needs on the lowest, most basic physiological levels are satisfied, there is little incentive to indulge the more spiritual desires. This is expressed in the following graphic:

The wise manager will ensure that these "motivational forces" are all given attention. He will recognise that satisfying the physiological needs by the provision of pay and other financial rewards is not enough. The importance of working conditions, the need for appreciation and respect, interaction with management and other staff, and being made to feel an important member of the organisation are all basic requirements.

On the other hand, it would be a grave mis-judgement to treat Maslow's theories, or those of other "gurus" of motivation (applied to business), as dogma. I'll refer to some of them shortly, but meanwhile it is appropriate, I think, to quote the words of Peter Drucker, probably the most highly regarded of all management experts, (of whom Tom Peters wrote: "Our debt to Peter Drucker knows no limit"), in his book Management:[4]

|

What Maslow didn't realize is that a want changes in the act of being satisfied. As the economic want is satisfied, that is, as people no longer have to subordinate every other human need and human value to getting the next meal, it becomes less and less satisfying to obtain more economic rewards. But economic rewards do not become any less important. On the contrary, while the impact of an economic reward as a positive incentive decreases, its capacity to create dissatisfaction, if disappointed, rapidly increases. Economic rewards cease to be 'incentives' and become 'entitlements'. If not properly taken care of - that is, if there is dissatisfaction with the economic rewards - they become deterrents. |

Douglas McGregor (1906-1964), a social psychologist of the behavioural school, believed that the way managers responded to their staff was influenced by certain assumptions. He suggested that behavioural patterns of people at work separated into two extremes that he designated Theory X and Theory Y.[5] Theory X was what McGregor called the "traditional view of direction and control"; Theory Y, which McGregor advocated, assumed a much more cooperative and reciprocal relationship between managers and workers, and was a starting point for Abraham Maslow's later theories, although Maslow considered that Theory Y made inhuman demands on the weaker members of an organisation.

The Theory X and Theory Y assumptions are described in the following Figure.

|

Theory X |

Theory Y |

| People dislike work and will avoid it if they can | Work is necessary to human psychological growth. People want to be interested in their work and, under the right conditions, they can enjoy it. |

| People must be forced or bribed to put out the right effort | People will direct themselves towards an accepted target |

| People would rather be directed than accept responsibility, which they avoid | People will seek, and accept, responsibility under the right conditions. The discipline people impose on themselves is more effective, and can be more severe, than any imposed on them. |

| People are motivated mainly by money. People are motivated by anxiety about their security. | Under the right conditions, people are motivated by the desire to realise their own potential. |

| Most people have little creativity - except when it comes to getting round management rules. | Creativity and ingenuity are widely distributed and grossly underused. |

Amongst other pioneers in the cause of achieving maximum motivation of commitment and the fulfilment of potential in business, Kurt Lewin developed the controversial concept of T-Group Training at the National Training Laboratories in Bethel, Maine, USA, in the mid-1940s, but died before the Maine experiments took place. The training involved much introspection and consequent disclosure to others of their fears and resentments, as well as the effect that the behaviour of others had on themselves.

This information was the basis of discussion on how people could best collaborate if they changed their behaviours. Despite the stress and emotional response that this induced in participants, often resulting in diminished rather than improved performance, the movement persisted, both at Bethel and at Britain's Tavistock Institute. [This was discussed at considerable length in Issues 7 and 8 of Nurturing Potential. Take a look at http://www.nurturingpotential.net/Issue7/Leader7b.htm#T-groups and http://www.nurturingpotential.net/Issue8/Further.htm to get an in-depth explanation of T-Group Training, or to refresh your memory if you already read it - Ed.]

The main implication of this in the development of management philosophy was the discovery that employees are more highly motivated and productive if they participate in working out how changes should take place. This was a revolutionary concept at the time.

Somewhat less revolutionary, but equally adaptable to the way in which managers and staff could best collaborate in order to achieve optimum development of potential, was Eric Berne's (1910-1970) Transactional Analysis (TA). with its emphasis on Ego States. These States (Child, Parent and Adult) represented behaviour patterns that make collaboration and cooperation difficult whenever two states failed to "mesh". Berne himself maintained that problems in staff relationships were exacerbated when people were in the wrong state to deal with a particular situation. Thus (to use the terminology of TA), "transactions" between people would inevitably fail when they were "crossed" (i.e. inappropriate), but could succeed when they were "complementary" (i.e. appropriate). Understanding Ego States (that is, understanding where the other person "is coming from" - and, indeed, the State you are in yourself - is a major key to profitable and constructive interaction between yourself and your "people".[6]

The following graphic illustrates the conditions pertaining to complementary and crossed transactions, where P = Parent, A=Adult and C=Child.

There are many more social scientists that I might refer to, in order to amplify this thesis, but I will content myself with just management guru Chris Argyris (Born 1923), Professor of Education and Organizational Behavior at Harvard Business School.

Argyris departs from the scientific management approach as ignoring the social and egotistical needs of the individual. He believes every individual should achieve his or her potential. Each of us has "psychological energy" which provides motivation. Our concern should not be how to create motivation, therefore, but where to channel it.

A major contribution to organisational learning and management techniques resulted from his development of his double loop theory of learning and organisational effectiveness. This was a logical step from his "theory in use" versus "espoused theory" studies. Argyris has explained this in an article in Organizational Dynamics, by the following analogy: "When a thermostat turns the heat on or off, it is acting in keeping with the program of orders given to it to keep the room temperature . . . at 68 degrees. This is single-loop learning, because the underlying program is not questioned. The overwhelming amount of learning done in an organization is single loop, because it is designed to identify and correct errors so that the job gets done . . . within stated policy guidelines. . .

"Whereas single-loop learning merely changes strategies and assumptions within a fairly constant set of norms, double-loop learning also questions the norms. It frequently involves conflict, either between established requirements or between individual managers and departments . . . each cycle where double-loop learning takes place helps create patterns for future learning."

Clear and unambiguous information has to be provided to avoid errors and channel motivation. In his work of 1992 [7] Argyris discusses the defences that individuals and organizations put up to resist double-loop learning. A chart shows how information may be provided both to defeat and enhance the nurturing of an individual's potential:

| [Error] | [Learning] |

| Vague | Concrete |

| Unclear | Clear |

| Inconsistent | Consistent |

| incongruent | Congruent |

| Scattered | Available |

In

the course of an interview by the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello of

Venezuela, in the early 1990s, Argyris stated: "Increasingly,

the art of management is managing knowledge. That means we do not manage people

per se, but rather the knowledge that they carry. And leadership means creating

the conditions that enable people to produce valid knowledge and to do so in

ways that encourage personal responsibility.

"Let me also say at the outset that I'm interested in action, and not simply knowledge for the purpose of understanding and explaining. . . The irony is that human beings can do both. They systematically do the first with what I call the espouse theory -- they espouse certain theories to explain what the world is about. But what really influences their actions are their "theories in use." These are designs that tell people how to behave in an organizational context."

|

. . . when executives deal with difficult, threatening, underlying issues, they use reasoning processes that, at best, simultaneously lead to immediate success and long-range problems. Often the problems go unsolved, compounding the long range difficulties. Much of this occurs without executives realizing it. [8] |

That concludes my brief introduction to some of the "gurus" of management and organizational method. There are many more. And I have only skimmed the surface material of those few individuals I have mentioned. Perhaps a further article in a future issue . . . ?

But to revert to my original thesis, at the end of the day, nurturing your people's potential is as much about nurturing your own, and defining and establishing where you are coming from in your interactions with your staff, your colleagues and your senior personnel, as it is about recognising their strengths and weaknesses.

![]()

[2] Laurence J. Peter and Raymond Hull - The Peter Principle, 1969. "In a hierarchy, every employee tends to rise to his level of incompetence."

[3] Robert Heller and Tim Hindle - Essential Manager's Manual, 1998.

[4] P.F. Drucker. Management. Pan, London, 1977.

[5] Douglas McGregor, The Human Side of Enterprise, McGraw Hill, 1964.

[6] Click here for the article on Transactional Analysis that appeared in Issue No. 3 of Nurturing Potential.

[7] Chris Argyris, On Organizational Learning, Blackwell Publishing, 1992.

[8] Chris Argyris, "The Executive Mind and Double-loop Learning", Organizational Dynamics, Autumn 1982.

![]()

Now assess your staff-nurturing ability

Never Occasionally Frequently Always

Score 1 Score 2 Score 3 Score 4

1. I persuade my staff rather than coerce them into enhanced performance.

2. I continually examine the need for improved working conditions.

3. I encourage people to air their grievances - and

4. I provide a regular forum for discussion by people.

5. I keep my staff fully informed about possible changes that might affect them.

6. I involve people in developments at an early stage.

7. I encourage people to act on their own initiative - but

8. I acknowledge my own responsibility for actions that are taken.

9. I explain my actions, particularly when they affect staff.

10. I avoid blaming, but insist on analysing reasons for failure.

11. I am always aware of my own needs and motivations.

12. I take a keen interest in my people's personal needs and motivations.

13. I delegate work wherever and whenever possible.

14. I keep a close watch for any examples of potential being under-utilised.

15. I consult subordinates, colleagues and senior personnel regularly.

16. I do not criticise encourage feedback.

17. I believe that regular change is preferable to maintaining policy rigidity.

18. I recognise merit and will reward it appropriately.

19. I regularly appraise performance and promote from within the company.

20. In appraisal meetings I encourage criticism of my own performance.

The maximum number of points you can score is 80. Any score between 60 and 80 is evidence that you are a strong motivator with highly developed potential-nurturing skills. It also suggests that you may be too complacent. Improvement is always possible. 40 to 60 points reveal a fairly sound motivational ability, with room for improvement. If you have scored below 40 points, performance is poor and your staff may be suffering. Examine particularly the areas where you have scored badly and try to adopt new methods and strategies.

![]()

[1] Terry Goodwin was a senior marketing executive at Finexport Ltd in London and Bangkok until his retirement in 1992, since when he has been in private practice as a marketing consultant.

* Graphical material and cross-references to articles previously published in Nurturing Potential have been provided by Joe Sinclair.