Another Fine Mess - a disordered education system

by Mark Edwards

Mark Edwards' biodata will be found at the end of the article, or by clicking here.

It’s

got to the stage that if I hear of another new form of ‘disorder’ afflicting

some poor child I’m putting myself on the passenger list for the first

spaceship to Mars. Apart from the fact that I find the word ‘disorder’

objectionable in itself, the mushrooming list of them means that it is going to

be a rare child indeed who goes through twelve years of education without

picking up at least one of these labels.

It

feels a bit like walking through a field full of those ‘sticky burr’ plants;

no matter how careful you are, one of them is going to attach itself to you

sooner of later. And they are buggers to shift once they are attached.

Ten

years ago Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder was virtually unheard of on

this side of the herring pond. In fact, when a mum and dad came to see me about

a placement for their ADHD daughter, they were pleasantly surprised that I had

heard of it. No other head teacher had, or if they had, it had been

dismissed as an American fad. Now it seems the tables are well and truly

turned, because in every school I visit, the medicine cabinet is bulging with

Ritalin.

It’s

not that I don’t think ADHD exists - I do. But in one case I know of, a

teenage child who has been diagnosed with it spends nearly every weekend

fishing. Unless I’ve

misunderstood, and this lad goes out into the Pacific Ocean in a speedboat

hunting the Great White Shark rather than fishing for tench and dace in the

River Exe, there is no way he has ADHD. No ADHD child could sit for hours

watching a piece of coloured plastic gently bobbing up and down in the water.

We

are potty about disorders in the UK, if you’ll excuse the phrase. My reasons

for objecting to the word are to do with the baggage that the word carries. It

implies several things - that it is something you are born with (try telling the

parent of a ‘disordered’ child that nurture might be as important as nature

- then start running); also it implies that the child cannot really do much

about it. This is manifest sometimes in children telling teachers that they

cannot avoid climbing on the school roof during literacy hour because they

‘have ADHD.’

I

have been working recently in a hostel for street people, most of whom have

addictions of one kind or another and many of them are diagnosed with mental

health problems. As one might expect, some of these conditions are extreme -

schizophrenia and psychosis for example. Now I have read several times that

these are genetically inherited conditions, but reading through the clients’

files, I note that one was raped by his father when aged 14 and another was

abandoned by his prostitute mother when aged two. Please don’t try to tell me

that these experiences have no bearing on their subsequent mental health

problems.

But many SENCOs (Special Needs Coordinators) and educational psychologists, whilst allowing for some environmental factors in child development, do in my view downplay the significance of children’s emotional experiences.

There are many reasons for this, most of them cultural. In the UK, we do not like to talk about our feelings. As psychologist John Heron puts it : “Our society is emotionally repressive. It has no working concept of the wounded child, no pervasive methods of emotional education and training” (Heron, 2001)*. There is a plethora of research suggesting how early experiences can have damaging consequences later in life, and that therapeutic interventions can help. But what happens is that schools notice the behaviour of a distressed or damaged child, apply a quick ‘off the peg’ diagnosis and set up a simplistic behavioural program, usually target-based, that has no real relevance to the child or his situation.

It

is a parlous state of affairs. Luckily, there are pockets of hope –

Southampton LEA for example have successfully pioneered a number of

‘emotionally literate’ projects and this is being noticed. However, it is

not enough – it is a drop in the ocean, and if you’ll excuse the extended

metaphor, a sea change is needed.

This

change needs to begin by recognising that we have feelings, both negative and

positive; that these feelings are connected to our thoughts, and that our

feelings and thoughts influence our behaviour. It’s hardly radical is it? But

you would think so judging by the general reaction to the idea of schools

employing counsellors on a routine basis, or the reaction of the Department for

Education to the idea that we might need to develop the notion of ‘emotional

competence’ in schools.

It’s

rather like trying to engage a sheep in a discussion about the role of metaphor

in the works of Moliere.

What

we need to do is broaden our understanding of Special Educational Needs. We need

to accept that children may have chaotic personal lives which prevent them from

learning effectively, and whilst putting a label such as ‘conduct disorder’

on the child might make US feel better, such a label is at best an irrelevance.

What would be far more useful would be to get to understand that child’s

personal construct of the world and devise a way forward which would enable him

to deal with the powerful feelings he is experiencing. That’ll take more than

a list of targets, and its probably more expensive in the shorter term.

But in the longer term, it’ll be cheaper than keeping him in that hostel I told you about.

* Incidentally, Heron seems to have given up the struggle – he now works in New Zealand.

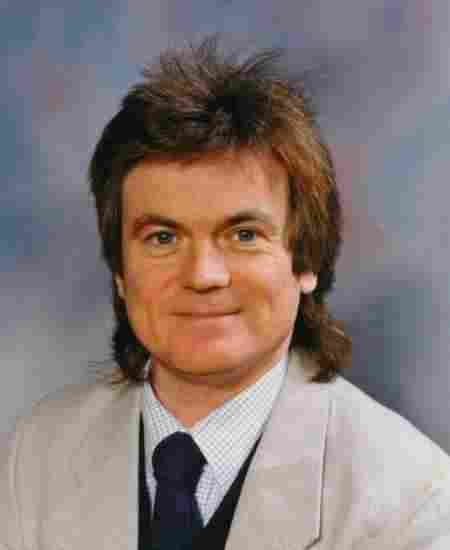

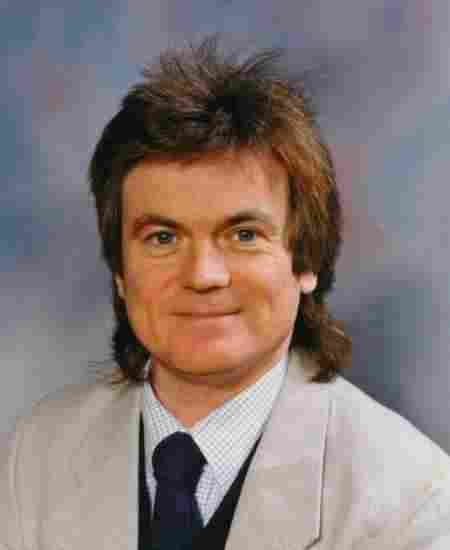

![]()

Mark Edwards was a headteacher, who still teaches part-time but combines this with writing articles, educational consultancy and entertaining people who like to hear badly performed rock, pop and music hall classics. He still carries a torch for child-centred education and is encouraged by the current interest in emotional literacy and thinking skills in schools. Mark is re-locating to Somerset, with his partner Liz, where he will continue his training in Integrative Counselling. He is a Master Practitioner in NLP (Psychotherapy). Email: Mark4Ed@aol.com.