LANGUAGE - A Nurturing Potential series

Part VI -CLICHÉS

[Avoid them like the plague]

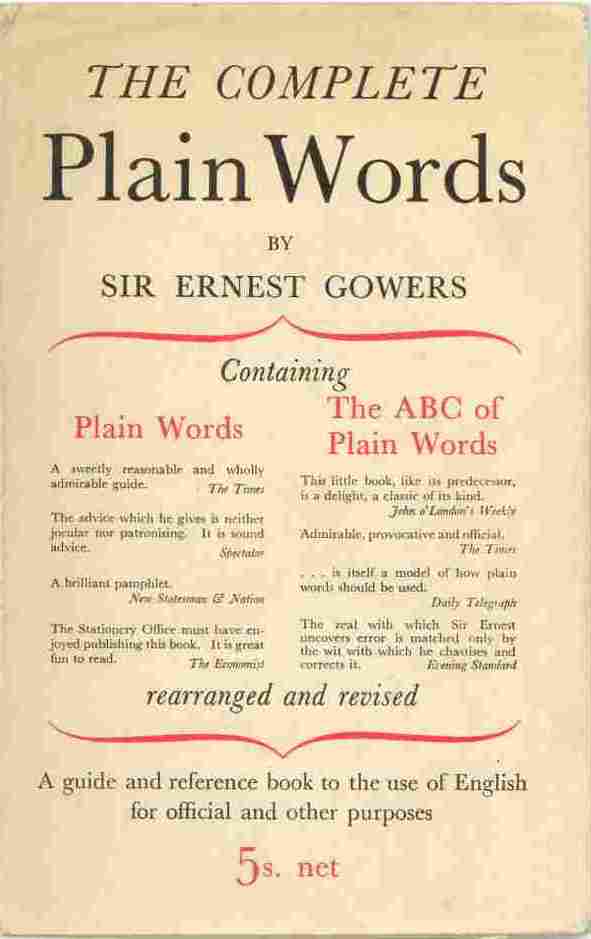

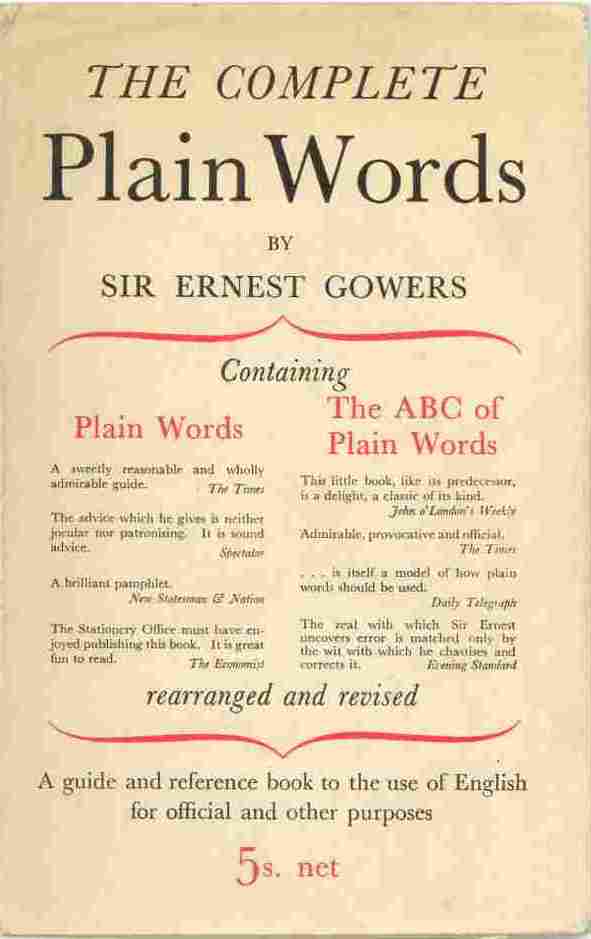

I recently purchased a secondhand, hard-bound edition of Sir Ernest Gowers' The Complete Plain Words to replace my battered loose-leaf (not by design) paperback copy. Before placing it on my shelves I glanced through it . . . and was immediately lost in nostalgic reverence. His words are as fresh as ever; his thoughts as commonsense. My eyes alighted on his section dealing with clichés and this served to remind me that the Language section of the next issue of Nurturing Potential still lacked an article. "Write it yourself, Joe" I said to myself. So here it is.

To digress for a moment from the topic of this article, I'd like first to write a bit about Gowers and his book.

The Complete Plain Words is a single volume containing the combined works Plain Words and The ABC of Plain Words. It was published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office in London in 1954. Both those works had been written at the invitation of the British Treasury in an attempt to improve official English as used by civil servants. The first of them was a general introduction to the subject; the second was intended as a work of reference. The author's intention, in writing these books, was well expressed by the G.M. Young quotation that heads his prologue: "The final cause of speech is to get an idea as exactly as possible out of one mind and into another".

The book is as current as ever. It is as useful as ever. It remains a sheer delight (oh dear, is that a cliché?) for anyone with the remotest interest in language, its simplicity as well as its complexity, its excitement as well as its frustration. What a pity the book never really achieved its intended outcome: civil service correspondence is as incomprehensible as ever to anyone who hasn't a first class honours degree in English . . . and even to most who have.

Gowers writes, "Professional writers realise that they cannot hope to affect their readers precisely as they wish without care and practice in the proper use of words. The need for the official to take pains is even greater, for if what the professional writer has written is wearisome and obscure the reader can toss the book aside and read no more, but only at his peril can he so treat what the official has tried to tell him."

When one considers that Plain Words was first published in the 1940s it seems incredible that Gowers could have come up with so much sensible advice that it has taken some linguists more than five decades to accept. And that, despite the fact that much of what Gowers proposed had been suggested by others centuries earlier. It would seem that in the area of language people tend to cling to outmoded concepts long after they have outlived any justification they may have had in origin.

A pair of examples. First:

Preposition

At End

Gowers writes: "It was, I believe, Dryden who invented the rule that prepositions must not be

used to end a sentence with. No one else of importance has ever observed it, and

it is now exploded. Whether a preposition should be put at the end of a sentence

or before the word it governs is a matter of taste in every case, and sometimes

taste will give unequivocal guidance. It is said that Mr. Winston Churchill once

made this marginal comment against a sentence that clumsily avoided a

prepositional ending: "This is the sort of English up with which I will not

put". The story is well known of the nurse who performed the remarkable

feat of getting four prepositions at the end of a sentence by asking her charge:

"What did you choose that book to be read to out of for?" She said

what she wanted to say perfectly clearly, in words of one syllable, and what

more can one ask?

"But the championship of the sport of preposition-piling seems now to have been wrested from the English nurse by an American poet:

|

"I lately lost a preposition; Correctness is my vade mecum,

|

Next:

Split Infinitive

"Too many people have already written too much about this. Of all that I have read on the subject, what I like best is the verdict of Jespersen, a grammarian who was as broad-minded as he was erudite.

| "This name is bad because we have many infinitives without to, as 'I made him go'. To therefore is no more an essential part of the infinitive than the definite article is an essential part of a nominative, and no one would think of calling the good man a split nominative." |

"Sir Sydney Cockerell has reminded us that Bernard Shaw is on the same side. Sir Sydney wrote to the Listener on the 4th Sept. 1947:

"About forty years ago Bernard Shaw wrote a letter to The Times very much as follows:

"'There is a busybody on your staff who devotes a lot of his time to chasing split infinitives. Every good literary craftsman splits his infinitives when the sense demands it. I call for the immediate dismissal of this pedant. It is of no consequence whether he decides to go quickly or quickly to go or to quickly go. The important thing is that he should go at once.'"

Clichés

Let us turn now (about time, did you say?) to clichés.

And I will start (where else?) with the definition given by Sir Ernest Gowers: A cliché is ". . . a phrase whose aptness in a particular context when it was first invented has won it such popularity that it has become hackneyed, and is used without thought in contexts where it is no longer apt."

Eric Partridge, whose Dictionary of Clichés was first published in 1940, and is highly praised by Gowers, writes: ""Haste encourages them, but more often they spring from mental laziness . . . [it is] an outworn commonplace; a phrase . . . that has become so hackneyed that scrupulous speakers and writers shrink from it because they feel that its use is an insult to the intelligence of their auditor or audience, their reader or their public. They range from flyblown phrases (explore every avenue), through sobriquets that have lost all point and freshness (the Iron Duke), to quotations that have become debased currency (cups that cheer but not inebriate), metaphors that are now pointless, and formulas that have become mere counters (far be it from me to . . . )."(2)

The point about clichés is not that they should be totally shunned, but they should never be employed simply because you are too lazy mentally to search for an original or more appropriate phrase. The cliché may well do an excellent job, but it will never have as satisfactory an effect on a listener or a reader as would a well-constructed sentence deriving from a writer or speaker with confidence in their own ability to produce an original statement.

My own most-hated cliché of the recent past was "At the end of the day . . . " which seemed to be included in every TV programme, particularly news and documentaries, and was a favourite form of evasion by politicians. It has recently, to my mind, been overtaken by the one-word cliché "Absolutely". Keep an ear out for the number of times you hear this daily as a response to a question, both in direct conversation and on the radio and TV.

![]()

As a footnote to this article, here are some amusing examples of clichés in the movies:

A detective can only solve a case once he has been suspended from duty.

A man will show no pain while taking the most ferocious beating but will wince when a woman tries to clean his wounds.

All bombs are fitted with electronic timing devices with large red readouts so you know exactly when they're going to go off.

Any lock can be picked by a credit card or a paper clip in seconds. Unless it's the door to a burning building with a child trapped inside

All beds have special L-shaped cover sheets which reach up to the armpit level on a woman but only to waist level on the man lying beside her.

These and dozens more will be found at http://www.harrisonline.com/heard/cliches.htm

![]()

And a final nod in the direction of Sir Ernest Gowers with his note on adjectives and adverbs: "Cultivate the habit of reserving your adjectives and adverbs to make your meaning more precise, and suspect those that you find yourself using to make it more emphatic."

![]()

And before "signing off" let me direct you to the book review section and, in particular, to the review. contributed by Sep Meyer, of The Oxford Dictionary of Euphemisms. Indeed, let me make life simple for you by suggesting that you simply click here.

![]()

[1] Morris Bishop in the New Yorker, 27th September, 1947.

[2] Eric Partridge, Usage and Abusage, Hamish Hamilton, 1947