Learning Difficulties (2)

(Concluding the main theme from our last issue)

1. Attention deficit disorder (ADD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

How Does ADHD Impact On Or With Other Disorders?

Treating ADHD - behavioural and pharmacological treatment

Treating ADHD - alternative treatment

What You Can Do to Help Your Child

3. Bibliography and links to sites of interest

![]()

Attention

deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

ADHD

is a frequently encountered disorder that affects children’s behaviour, but

is often difficult to diagnose. Although

there are a number of common symptoms, many of them occur to a smaller or

greater extent in all children. All

children have difficulty paying attention, following directions, or being

quiet from time to time, but for children with ADHD, these behaviours occur

more frequently and are more disturbing to the children and those around them.

One

of the most common of these is an inability to concentrate or focus.

Children with ADHD tend to be impulsive and easily distracted; they

find it hard to sit still and pay attention in school.

Originally

simply called ADD (Attention Deficit Disorder) it was renamed in 1994 by the

addition of “hyperactivity” in deference to this particularly frequent

behavioural symptom.

1.

The more common symptoms of ADD are:

► carelessness

in schoolwork and other activities;

► inability

to sustain attention in tasks or play activities;

► apparent

listening problems;

► difficulty

following instructions;

► difficulty in organizing tasks and activities;

►

dislike

of and avoidance of tasks that require mental effort;

► tendency

to lose things like toys, notebooks, or homework;

► ease

of being distracted;

► forgetfulness

in daily activities.

2.

Further symptoms that occur in ADHD subjects include:

► fidgeting

or squirming;

► difficulty

remaining seated;

► excessive

running or climbing;

► difficulty

playing quietly;

► an

excess of energy;

► excessive

talking;

► answering

questions before they have been completed;

► difficulty

waiting for a turn or in line

► frequently

interrupting or intruding

3.

Subjects may also be encountered who display a combination of some symptoms

from each of these categories.

To

be diagnosed ADHD, a child will habitually display these behaviours before age

7 and they will persist for at least 6 months. The behaviours will also have a

negative effect on at least two areas of a child's life (such as school, home,

or friendships).

No

one cause of ADHD has been identified. It

is known that there are biological origins to ADHD, but these have not been

clearly defined. There is also

evidence to support the belief that some children have a genetic

predisposition towards ADHD, as it would appear to be more common amongst

children who have close relatives with the disorder.

There is also some statistical evidence to relate ADHD to smoking or

substance abuse by the mother during pregnancy.

A

variety of early theories have been debunked over the years.

These include poor parenting, family problems, poor schools or

teachers, too much TV, food allergies, excess sugar, even that it was caused

by minor head injuries or damage to the brain.

Indeed, for many years ADHD was known as “minimal brain damage”

despite a lack of evidence of head injury or brain damage.

Another theory would link the intake of refined sugar and food

additives to hyperactivity and inattention, but scientific research merely

resulted in a suggestion that this may apply only to a small percentage of

very young children or children with food allergies.

More

and more the evidence from scientific and medical research is tending towards

the conviction that ADHD is more likely to derive from biological factors,

influencing neurotransmitter activity in parts of the brain and having a

strong genetic and environmental origin.

And more and more the evidence is suggesting that environmental factors

have little or no relationship to the origin of the condition, although they

may result in behaviour that resembles and may be misdiagnosed as ADHD.

For example, children who have moved home or school, or have been

involved in a divorce, or other significant life event may display impulsive

and over-active behaviour, forgetfulness and absent-mindedness. But it is

important not to confuse this behaviour with ADHD, even though the symptoms

may be similar. After all, not

all children with ADHD come from dysfunctional families, nor do all children

from unstable or dysfunctional families have ADHD.

The

genetic relationship to ADHD, however, does have some statistical evidence to

support it. There is apparently a higher predisposition to ADHD if

other family members also have ADHD. This

may be of the order of a 25 to 35 per cent probability that if one person in a

family is diagnosed ADHD, another family member will also have the disorder.

Research

into the neurobiological origins of the ADHD attributes the symptoms to a

chemical imbalance in the brain that interferes with the ability to focus and

sustain attention, as well as with memory formation and retrieval.

The brain has a network of billions of nerve cells. Each of these is linked to hundreds of other nerve cells.

Each nerve cell terminates in a projection known as an axon (the part

of the cell that sends messages to other cells) and many dendrites (the part

that receives messages from other cells). There is a gap between the axon and

the next nerve cell; they do not connect or touch. This neural gap is called a

synapse.

|

|

Since

these nerve endings don't actually touch, special chemicals called

neurotransmitters carry the message from the end of the axon to the dendrites

that will receive it. This stimulates the next cell to start an electrical

impulse of its own. With ADHD there is a flaw in the way the brain manages the

neurotransmitter production, storage or flow, causing imbalances. They are

either insufficient, or the levels are not regulated, swinging wildly from

high to low.

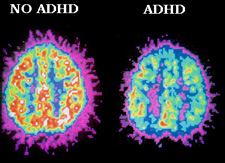

Although scientists are not sure whether this is a cause of the disorder, they have also found that certain areas of the brain (in the frontal lobes and basal ganglia) are about 5% to 10% smaller in size and activity in children with ADHD. Differences between ADHD-affected and non-ADHD individuals were marked by Positron Emission Tomography (PET) brain scans, revealing the activity in the frontal lobes.

|

How Does ADHD Impact On Or With Other Disorders?

An added difficulty in diagnosing ADHD is that it often coexists with

other problems. Nearly half of all children with ADHD also have Oppositional

Defiant Disorder, which is characterized by stubbornness, outbursts of

temper, and acts of defiance.

|

"Young children are oppositional from time to time. They may talk back to parents and teachers and occasionally strike out at peers. However, when openly uncooperative or aggressive behaviour is strikingly different compared with other children of the same age and developmental level, it can be a cause for concern. The diagnostic term for this condition is oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). It would be prudent for Jason to have a comprehensive evaluation to determine whether he has this disorder or another, such as ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), a mild learning disability, a mood disorder such as depression, or an anxiety disorder." |

Mood

disorders, such as depression, are commonly seen in children with ADHD, and

may be the direct result of having ADHD. They feel inept,

socially isolated, and frustrated by school failures. A little extra help in

social and academic areas can go a long way in helping to alleviate this type

of depression.

Other

children may have a mood disorder that exists independently of ADHD, which may

require additional psychotherapy or medication.

Many

children with ADHD also have a specific learning disability, which

means that they might have trouble mastering language or other skills, such as

mathematics, reading, or handwriting. The most common learning problems are with

reading and handwriting. Although ADHD is not categorized as a learning

disability, its interference with concentration and attention can make it even

more difficult for a child to perform well in school.

- behavioural and pharmacological treatment

Because ADHD is often confused with other disorders it is essential that it is properly and adequately diagnosed.. Only after the presence of ADHD is determined should options for treatment be explored. These will typically comprise a combination of behavioural therapy and medication therapies. Behavioural therapy will include the organisation of the child's environment with the collaboration of parents and teachers, as well as some application of traditional behaviourist theory of rewards, disincentives, physical activities, and the teaching of social skills.

The behavioural therapies include dividing large assignments into smaller more manageable tasks, providing rewards for completing certain tasks, speaking with a therapist, finding a support group, and manipulating situations to benefit the child’s needs, such as giving the child no time limits while taking a test, seating the child away from as many distractions as possible, and giving the child less homework.

Medication remains a first-line option and all the medications approved for the treatment of ADHD work by increasing the amount of either or both of the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine, a deficiency of which has been attributed to the defective genes associated with ADHD. It is usually suggested that medication should not be used without behavioural therapy.

Mark Selikowitz in his excellent book ADHD the facts[1] (reviewed in this issue of Nurturing Potential) devotes one section to a variety of treatments under the separate categories of Home Management, School Management, Behaviour Modifications and Medicines. In the specific chapter dealing with general medicine treatment he has provided a useful table comparing the action of various types of medication on the levels of dopamine and/or norepinephrine in the synapse:

|

Medication |

Major action in ADHD |

|

Methylphenidate [Ritalin] |

Blocks dopamine transporter |

|

Dexamphetamine |

Releases dopamine from storage vesicles |

|

Imipramine [Tofranil] |

Inhibits re-uptake of norepinephrine |

|

Clonidine [Catapres] |

Blocks norepinephrine autoreceptors |

|

Atomoxetine [Strattera] |

Inhibits re-uptake of norepinephrine |

|

Moclobemide [Aurorix] |

Inhibits breakdown of dopamine and norepinephrine by monoamine oxidase |

|

Risperidone [Risperdal] |

Blocks dopamine autoreceptors |

What this demonstrates, Selikowitz points out, is that a particular medication that will help one child with ADHD, may not, ipso facto, help another, or that other children may require several medicines. And this, of course, simply verifies what medical practitioners have discovered from observation and research.

|

Pharmacological treatments are the most widely used treatment of ADHD and stimulants such as Ritalin are by far the most common medication. The medication provides a short term suppression of the classical symptoms of ADHD, thereby allowing the children to focus at home and in class without being disruptive.

A great deal of research has been done on these medicines, mostly on Ritalin. Certainly in the UK and the USA it is Ritalin that has received the greatest publicity and borne the brunt of most criticism, for while these medicines have the potential to alleviate the difficulties of children with ADHD - in some cases dramatically - they have also provoked considerable controversy around the issue of unacceptable side-effects. These include loss of appetite, irritability, insomnia, headaches, stomach pains, nausea and drowsiness. While most of these conditions are not serious, or life-threatening, and usually persist only for a short time, it has been contended that more harmful effects may be attributed to Ritalin, including its potential for abuse and addiction.

[More on this aspect of Ritalin may be found at http://www.add-adhd-help-center.com/ritalin_side_effects.htm ]

There are several other concerns. Stimulant medication is short-term in operation, the disadvantage of each dose being effective for only about four hours is that several doses may be required each day. Also the consequences of treatment being continued for more than about 14 months are still being evaluated. But the major concern may be the readiness with which teachers, parents, and medical practitioners prescribe and/or use stimulant medicines as an easy option. The fact that the majority of children given a dose of, for instance, Ritalin will promptly, albeit for a limited period, discard their disruptive, anti-social, or inattentive behaviour may simply encourage the dispensation of the drug without sufficient regard for alternative - perhaps longer-term - remedies.

|

"Some children, of course, have problems so severe that drugs like Ritalin are a godsend. But that has little to do with the most obvious reason millions of American children are taking Ritalin: compliance. One day at a time, the drug continues to make children do what their parents and teachers either will not or cannot get them to do without it: Sit down, shut up, keep still, pay attention. In short, Ritalin is a cure for childhood." Mary Eberstadt (Reading, Writing, and Ritalin)an anxiety disorder." |

[Further concerns over the use and effectiveness of Ritalin may be found at the website of Dr.Peter Breggin, in a summary taken from his book Talking Back to Ritalin: http://www.breggin.com/ritalinbkexcerpt.html]

|

In Britain, Liberal Democrat health spokesman Paul Burstow has urged ministers to examine why the number of prescriptions has increased so sharply. "There is a very big debate about the rights and wrongs of Ritalin but we need to look at why the prescription rates have gone up so steeply. It has become the option of first choice rather than a last resort for some families, but it needs to be given appropriately and only if it is really necessary," he said. "There are still questions over the implications of giving such a powerful and illicit drug to very young children." |

Treating ADHD - alternative treatment

In a study carried out some time ago parents of ADHD children were asked to speak about the use of complementary and alternative medicine initiatives they had adopted with their children. The report on this study stated: "We know, that a lot of parents will try them to make every possible attempt to avoid psychopharmacological treatment with psychostimulants or other forms of multimodal treatment. 62 of 114 (54%) of the parents had experiences with this kind of treatment. Reasons to make a trial of this type of treatment were mainly: a "natural" alternative; and having more control over the treatment.

"One important result of the study was that only 14 % of the parents talked about their treatment approach with their doctor. This might cause severe problems for the children because even "natural" approaches like nutritional supplements or dietary manipulations or even high-dose vitamins can cause severe problems or interactions with medicine. . .

"Up to this point of research there is no alternative or complementary treatment for ADHD that proved any lasting positive results. You should be very careful if advertisements or laymen recommend this type of treatment and promise a "cure" for ADHD symptoms."

But while it is correct to issue a warning about trying alternative methods of treatment without sufficient and tested evidence of the efficacy and safety of the treatment, particularly in these times of such vast internet promotion of "nostrums and potions", it would be incorrect to dissuade parents from trying alternative treatment pari passu with conventional pharmacology. According to CHADD [see below], "The good news is that the Internet is becoming an excellent source of medical information. The bad news is that with its low cost and global entry, the Web is also home to a great deal of unreliable health information."

The CHADD[2] website suggests the following definitions for the various treatment options:

Medical/medication management of AD/HD refers to the treatment of AD/HD using medication, under the supervision of a medical professional.

Psychosocial treatment of AD/HD refers to treatment that targets the psychological and social aspects of AD/HD.

Alternative treatment is any treatment — other than prescription medication or standard psychosocial/behavioral treatments — that claims to treat the symptoms of AD/HD with an equally or more effective outcome. Prescription medication and standard psychosocial/behavioral treatments have been “extensively and well reviewed in the extant literature, with undoubted efficacy.”1

Complementary interventions are not alternatives to multimodal treatment, but have been found by some families to improve the treatment of AD/HD symptoms or related symptoms.

Controversial treatments are interventions with no known published science supporting them and no legitimate claim to effectiveness.

CHADD goes on to say: "Before actually using any of these interventions, families and individuals are encouraged to consult with their medical doctors. Some of these interventions are targeted to children with very discrete medical problems. A good medical history and a thorough physical examination should check for signs and symptoms of such conditions as thyroid dysfunction, allergic history, food intolerance, dietary imbalance and deficiency, and general medical problems that may mimic symptoms of AD/HD."

Here are some of the alternative treatments with a brief explanation of each:

Dietary Intervention: consists of the elimination of one or more foods from the diet. This is on a par with finding and eliminating a source of allergy.

Nutritional supplement: consists of adding one or more foods to the diet in the belief that the complaint is caused (or exacerbated) by the absence of a specific nutrient.

Sensory Integration Therapy: is normally provided by occupational therapists and addresses the situation where the brain is overloaded by too many sensory messages and cannot normally respond to the sensory messages it received.

EEG Biofeedback: also known as neurofeedback, it is based on the discovery that many ADHD individuals show low levels of arousal in frontal brain areas. Individuals are taught to increase arousal levels in these regions and it is anticipated that this will lead to improvements in attention and reductions in hyperactive/impulsive behaviour. "Many parents report that it has been extremely helpful for their child. There have also been several published studies of neurofeedback treatment that have reported encouraging results." [CHADD op.cit.] .

Chiropractic: which is based on the belief that spinal problems are the cause of health problems and that imbalance of muscle tone can cause an imbalance of brain activity. Spinal adjustments, it is believed, as well as other somatosensory stimulation, such as exposure to varying frequencies of light and sound, can effectively treat ADHD and learning disabilities.

Other Treatments: include meditation, neuro-linguistic programming techniques (for specific areas), emotional freedom techniques (for specific areas).

It may be useful to note, in finishing this section, the concluding paragraph of a study by the American Psychiatric Association in 2002:

. . . "the study's findings suggest that non-traditional treatments for ADHD symptoms merit further study. Future research should examine the full array of potential complementary and alternative medicine services, including interventions that contain commonly available regional medicinal plants, and should be geographically more diverse to allow broader generalization of findings. Results of such studies could inform future editions of ADHD practice parameters on how to address non-traditional interventions. In the meantime, our findings indicate that health care providers should routinely inquire about the use of complementary and alternative medicine for children with ADHD or in whom ADHD is suspected. Parent education should not only address the evidence base of traditional therapies but also make reference to commonly selected non-traditional methods and comment on the limitations of the Internet as an information source."

What You Can Do to Help Your Child

[A number of suggestions culled from various sources]

ADHD affects all aspects of a child's home and school life. Specialists

recommend parent education and support groups to help family members accept

the diagnosis and to teach them how to help the child cope with frustrations,

organize his environment, and develop problem-solving skills.

Adjustments

may be necessary for your child in the classroom. She might be able to pay

better attention, for example, if she sits in the front of the room, has an

extra set of books at home, and is given additional reminders to complete

tasks.

Modify

the environment in an effort to reduce distractions. "Open"

classrooms do not work well for children with ADHD because sitting around

tables or in groups is more distracting that sitting in rows. Talk to your

child's teacher about decreasing noise and clutter in the classroom.

Provide

clear instructions. Ask your child's teachers to have your child write down homework assignments in a notebook, and check that it is complete. Both

you and your child's teacher should keep oral instructions brief and provide

written instructions for tasks that involve many steps.

Focus on success. Provide formal feedback (such as a star chart) to reinforce your child's positive behaviours and reward progress even if it falls a little short of the goal.

Help

your child organize. Encourage your child to establish daily checklists, and

remind him to check his homework notebook as the end of the school day to make

sure that he takes the correct supplies and textbooks home.

Encourage

performance in your child's areas of strength, and provide feedback to her in

private. Do not ask your child to perform a task in public that is too

difficult.

Encourage

active learning. Teach your child to underline important passages as he reads

and to take notes in class. Encourage your child to read out loud at home if

fluency and comprehension are a problem.

FINALLY WE WOULD SAY: Do not take the easy way out. There is a vast array of physiological and psychological conditions that may resemble ADD/ADHD. It may be reassuring to parents to have a medicine such as Ritalin prescribed and apparently successfully reduce or inhibit a child's tendency to behave in a "socially unacceptable" way, or to distract its parents from the enjoyment of their own leisure time at the end of a tiring day. Please do not presume that, because this makes things easier for you at that time, it will inevitably be the best way out for your child. Explore all the other avenues. Allow prescription drugs to be prescribed, by all means, but simultaneously check alternative ways of dealing with the situation. The day may come when you and your child will be grateful.

![]()

[1] ADHD the facts by Mark Selikowitz. Oxford University Press, 2004,

[2] Children and Adults with

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. http://www.chadd.org/

(Fact Sheet 6)

![]()

There are generally reckoned to be five pervasive development disorders (PDDs) of which Autism is one. Others are Asperger's Syndrome, Rett's Syndrome, Childhood Disintegrative Disorder (CDD), and PDD-NOS (Pervasive Development Disorder - Not Otherwise Specified). Each of these disorders has specific diagnostic criteria, but all are characterised by "severe and pervasive impairment in several areas of development" [1] including verbal and non-verbal communication, social interaction, and leisure or play activities.

Autism is the most common of these five disorders and affects between 2 and 5 per 1000 individuals in America (according to a statistical study undertaken in 2001). There is statistical evidence to demonstrate that this incidence is consistent with the situation in other countries, that the disorder crosses racial, ethnic and social boundaries, and is not affected by wealth, lifestyle, or educational level. It is also four times more prevalent in males than females.

There is no single cause, but it is believed to result from abnormalities in brain structure or function. Brain scans show differences in the shape and structure of the brain in autistic and non-autistic children.[2] Research has been proceeding on a number of lines such as a connection with heredity and genetics. Although no single gene has been identified as causing autism, the possibility does exist that autistic children may have inherited the condition.

The possibility of a relationship between vaccines and autism also continues to be the subject of debate and, at the time of writing this article in the UK, it has become a very hot political "potato".

What seems beyond doubt is that children with a PDD such as autism are either born with the disorder, or born with a propensity to it. It is not a mental illness, it does not derive from bad parenting, and children displaying unsocial behaviour are not simply being unruly.

There are apparently no medical tests for diagnosing autism. Diagnosis is based on observation of the individual's communication, behavioural and developmental levels. There is, however, a strong possibility of symptoms being confused with those shared by other disorders and, in such case, some medical tests may be adopted to rule out the possibility of another cause of the displayed symptoms.

Diagnosis is further complicated when someone with autism may appear to be mentally retarded, display a personality disorder, have a problem with hearing, or behave in an odd or eccentric way. This is rendered even more difficult because, although these conditions may have nothing to do with autism, yet they may co-occur with autism. It is therefore important to distinguish autism from other conditions in order to ensure accurate diagnosis.

Early diagnosis is important and there are a number of characteristic behaviours by infants, but more usually in early childhood, that may ring a warning bell. These include:

► Failure of an infant to babble or coo during first year.

► Failure of an infant to gesture, point, wave or grasp during first year.

► Failure to say single words by 16 months.

► Failure to say two-word phrases on their own by 24 months.

► The loss of any language or social skill at any age.

An autistic person is an individual and, like all individuals, is unique and will display characteristics that will not necessarily duplicate those of other persons with autism. Some may have greater difficulties with social interaction, but less difficulty with language. Others may exhibit the reverse. Initiating and maintaining a conversation may be difficult; "hogging" a conversation is a recognised symptom, as is "butting-in" to other people's conversations. Response to information furnished by others may also vary from individual to individual, with aggressive and/or self-injurious behaviour being displayed.

Other traits may include:[1]

► Insistence on sameness.

► Difficulty in expressing needs; uses gestures or pointing instead of words.

► Repeating words or phrases in place of normal, responsive language.

► Laughing, crying, showing distress for reasons not apparent to others.

► Preferring to be alone.

► Tantrums.

► Difficulty in mixing with others.

► Not wanting physical contact.

► Little or no eye contact.

► Unresponsive to normal teaching methods.

► Inappropriate attachment to objects.

► No real fears of danger.

► Noticeable physical over-activity or under-activity.

► Not responsible to verbal cues; acts as if deaf although hearing tests in normal range.

This is one of the five pervasive development disorders (PDDs) described in the first paragraph of this section on Autism. Diagnosis of this condition is apparently on the increase, but whether this is due to more effective diagnosis or simply that it is becoming more prevalent, is unclear.

Asperger's disorder was first recognised by the Viennese paediatrician Hans Asperger in the early 1940s and he went on to publish his findings within one year of the publication of the similar study on Autism by Kanner in America, neither man aware at that time of the work of the other.

Although there are clear similarities between the two conditions, both displaying similar behaviour patterns and similarly flawed communication and social skills, and affecting mainly males, there are also very distinct differences, both in the severity of symptoms and in language delays. Children with Asperger's disorder may be only mildly affected and frequently have good language skills; they merely tend to use language differently: unusual speech patterns, rather formal speech, speaking too loudly, having difficulty comprehending the subtleties of language such as irony and humour.

Another difference between Asperger's and autism is in the area of cognitive ability. By definition, a person with Asperger's Disorder will possess average to above average intelligence, although some children with Asperger's Disorder may display motor skill delays and appear awkward and clumsy.

According to the Autism Society of America, [1] "Children with autism are frequently seen as aloof and uninterested in others. This is not the case with Asperger's Disorder. Individuals with Asperger's Disorder usually want to fit in and have interaction with others, they simply don't know how to to it. They may be socially awkward, not understanding conventional social rules, or may show a lack of empathy. They may have limited eye contact, seem to be unengaged in a conversation, and not understand the use of gestures."

[An excerpt from Kevin Phillips's unique website http://www.angelfire.com/amiga/aut/links.html - Kevin's personal contribution to this issue of Nurturing Potential may be found at http://www.nurturingpotential.net/Issue11/Autism.htm]

|

"It must be remembered that just because someone can't communicate effectively, it doesn't mean they have nothing worth saying. It doesn't mean they have nothing to contribute. Some people who can talk fluently are capable of talking gibberish and nonsense." |

Most people with Asperger's Syndrome are denied help by Social Services and the Benefits Agency because they have an average or high IQ. So with Autistic Spectrum conditions the lower your IQ is, the better chance you have of receiving help. Would they say to someone who is Blind or Cerebral Palsy and who has an IQ of 140 that they don't need help? Since when did being blind or deaf and having an high IQ stop them from receiving benefits and support? What if you are Autistic and have an IQ of 68 and later score 71?

When

I was 16, my intelligence level was that of a 16 year old or above. My emotional

maturity was that of a 16 year old but my interaction and social skills were

like those of a 6 year old at best. I didn't know how to hold or maintain a

conversation. I didn't understand interaction and how to communicate in the NT[3]

way. Now I would put my social and interaction skills, which have improved over

the years, at about the level of a 15 year old.

I find it very hard to work to maintain them at this level but they are unrecognisable now to how they were in 1992. If IQ's were measured in social interaction and social skills, when I was 16 I would have scored about 30. Now my social skills IQ would be at about 80. The average IQ level is 100.

Things I have learned to do in more recent years when in conversations include turn-take, which I didn't have a clue about in 1992. I would have butted in then and talked relentless about something. I have learned if in company and someone says something funny and I don't find it funny, to give a quick grin and move on. In 1992 I would have just sat there with a blank unchanging facial expression. I couldn't even read facial expressions at that stage of my life. I can read them today, with difficulty, but at least I can.

It is no longer acceptable for Education Authorities to say there are no Autistic children in their town. It is no longer acceptable anywhere in England. It is no longer acceptable anywhere in Northern Ireland. It is no longer acceptable anywhere in Scotland. It is no longer acceptable in Wales. It is no longer acceptable anywhere in the USA. It is no longer acceptable anywhere in Canada and it is no longer acceptable anywhere in Australia.

It is no longer acceptable for schools to suspend Autistic kids for merely defending themselves against out of control kids who intend to use extreme violence on them.

It is no longer acceptable for Disability Employment Advisers to not know what Asperger's Syndrome is.

Despite the improvements of the last few years, much more needs to be done for Autistic Spectrum people and it needs to start now.

Children and adults with Autistic Spectrum Conditions both deserve a life not a life sentence.

It must be remembered that just because someone can't communicate effectively that it doesn't mean they have nothing worth saying. It doesn't mean they have nothing to contribute. Some people who can talk fluently are capable of talking gibberish and nonsense.

![]()

[2] See also the earlier section on ADD/ADHD.

[3] Neurotypical syndrome is a neurobiological disorder characterized by preoccupation with social concerns, delusions of superiority, and obsession with conformity. [Ed.]

![]()

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND LINKS TO SITES OF INTEREST

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

There are many books available on these subjects - many more, indeed, than was the case until fairly recently - and new works are being produced regularly. Some of these are reviewed in our own review section: http://www.nurturingpotential.net/Issue11/Bookreviews11.htm.. For older works of reference you might try http://www.angelfire.com/amiga/aut/books.html taken from Kevin Phillips's website.

We would like to draw readers attention, however, to one book that has not yet been published, and express our thanks to Sage Publishing for having provided us with proofs of Kate Wall's Autism and Early Years Practice, due to be published by their associates Paul Chapman Publishing in April 2004. We found this to be a remarkable reference resource for preparing our leading article for this issue. It is, without a doubt, the most absorbing and easily absorbed book we have seen, setting out the most comprehensive survey of the history, definitions, needs of carers and sufferers, issues of diagnosis, and much, much more.

We would also like to praise the excellent quarterly journal published by Sage in collaboration with the National Autistic Society. The journal Autism (The International Journal of Research and Practice) is now in its 8th year and its excellent quality remains undiminished.

LINKS:

We permit ourselves a piece of nepotism here by recommending our own correspondent Kevin Phillips website, which itself provides a source of further links: http://www.angelfire.com/amiga/aut/links.html.

For access to specifically UK sources of information about Autism and Asperger's Syndrome http://www.healthcentre.org.uk/hc/pages/autism.htm

Balancing this with a specifically American site of interest: http://www.support4hope.com/autism/aspergers.htm

The main UK site, however, is http://www.nas.org.uk/ and the main American site is http://www.autism-society.org/site/PageServer