Ventoux

by John Ewing

[John's biodata and picture follow the article]

On 8th June this year I cycled up Mont Ventoux, in Provence [a]. Some

email friends, who gently ridicule my cycling, expressed doubts about my

sanity

and asked why on earth I should inflict such torture on myself when armchairs

and email are so much more comfortable. This was my answer.

![]()

What was it all about, and why do it? Part of the answer lies in the

old cliché, that if it's worth doing, it's worth doing well. At my age,

"well" doesn't mean winning contests, or going faster or further

than someone of 25, it means setting goals and achieving them: my first 100-km

ride, my first 200, my first 1000-metre climb, my first 10% climb, etc.

Usually, I set these goals for myself then find the event to suit. If there isn't one, then I plan a route and do it alone, or with someone else if I can drag them along. The Ventoux goal, however, came from outside, last November when a member of my club committee mentioned that he and some pals were going to the Vaucluse to climb the Ventoux, and who would like to go? I said yes immediately, knowing that it would be by far and away the hardest thing I had ever done, but that there would be six months to prepare in between.

In March the whole group convened to thrash out routes: we would be a week in the South, and would be riding every day: a couple of warm-up rides over lower cols were planned before the main effort, then a day off to change hotels followed by a couple of easy rides over lower cols and scenic routes to recover.

I came out of that meeting with a certain foreboding. I take metformin for the diabetes, and one of its major effects is to fool the muscles into using up their glycogen reserves, so that they extract glucose from the bloodstream to replace it. In doing this, they create large quantities of waste products, the worst of which is lactic acid, that has to be flushed away by the bloodstream before it builds up into Jane Fonda's famous "burn". Lactic acid is produced by exercise anyway, so when you engage in heavy exercise on top of metformin you not only use up your reserves faster than normal, you produce the normal load of lactic on top of the metformin's quota. Once you deplete the reserves your muscles consume their own protein and produce even more lactic; but before that you go into quite severe cramps. This has always been my bugbear in cycling: I can manage two days in a row, but at some point on the second day I know that cramp will set in, and that on the third day my muscles will hurt like hell and have the efficiency of mincemeat.

And here we were, planning to climb Mt. Ventoux on the third day.

I spoke to the doc a couple of weeks before we left, and obtained his gracious permission to cut the medicine out for that week. I had no idea, however, how effective this would be.

Concerning Mont Ventoux: known as the Giant of Provence, this mountain is high enough to generate its own weather and experience high winds around the summit while the rest of the surrounding country is in a flat calm. There are three approaches: the easiest via a town called Sault, a leisurely 4.7%[1] over 28km, 21km via Malaucène at an average 7.3% and the hardest, 22 km from Bédoin, at 7.5%. This is generally known as one of the hardest climbs in France, the only worse one being the Alp d'Huez - and even then, this is debatable: Alpe d'Huez has an average slope of 8.5%, but you climb a total of only 1103 metres: to get up the Ventoux from Bédoin you have to climb over 1600.

At dinner on our first evening we met a Belgian rider who had done it the year before and was back to do it again: his main comment was "c'est trés dur" - it's very hard. Over the course of the next two days we met yet other riders who had been there: "trés dur" was the leitmotif, the variations being "trés, trés dur" and "incroyablement dur". One guy just shook his head and said "dur", but he said it three times.

And here we were, planning to climb Mt. Ventoux on the third day...

The first two days' rides were fairly stiff. On the first day we totalled 85 km and around 1500 metres of climbing in the nub-end of the Mistral, on the second 85 km and around a thousand metres with no wind. The problem with the second day was that many of the metres climbed were on false flat, which cyclists heartily detest: a false flat is a gentle slope that appears flat, so that you go at it expecting to ride at normal speed. When you don't, you try harder and harder for little return on investment. You can flog yourself to death on a 1% slope just as easily as on a 15%er.

I managed the two days without cramp, but that day two sortie, intended to be gentle, was a killer. With no Mistral the temperature rose into the 30s (30°C = 86°F) and the kilometres seemed to stretch for ever. I had pretty bad sunburn from the first day - high-factor sunblock mixed with sweat turns into something like modelling clay, so I don't use it - and just about every part of me felt the grind of those long false flats. In this depleted and irritated state, the couple of real climbs we did were hell. If on the first night we had all been lively at dinner, that night we were pretty dumb: knocked out and staring into space. We haggled out the logistics for the next day - we would be RVing with cars carrying extra water and cold-weather clothes in case the weather should turn - and crawled off to bed feeling utterly dead.

The next morning, 8th June, was The Day. My muscles, surprisingly, did not feel too bad, but the insertions - the bits where they bind to the bone - were sore to the touch. So don't touch them, I decided. Breakfast was all gallows humour, with our Belgian cyclist friend sitting a couple of tables away nodding sagely.

We set off: sharply downhill for a few kilometres, then a long shallow climb up to Bedoin, at just about the same height as our hotel. Surprisingly, my legs didn't feel too bad, but I wasn't about to start tearing up the tarmac. Everyone kept a very sedate pace, in any case: a mere 16 kph as opposed to the 25 we usually set out with on our jaunts. We cruised through the centre of Bedoin, then on out the other side to a crossroads, where we halted for a last drink together and a photo before the climb.

So who's on the photo? The names will mean little, but for the sake of record there was (R to L) Armand (55), truck-driver and trader in fine art, with a collection of over 400 paintings at home; Augustin (58), a Spanish pal of his; Roland (56), foreman in a boilerworks and our strongest rider; Bernard 2 (64), retired; Bernardette (59), wife to Bernard 2; René (45), the sig. other of Roland's daughter; Bernard 1 (60), retired, who organized the whole thing; and Jean-Pierre (56), manager of a home for refugees. I myself (57), sometime programmer, was behind the shutter. Solange, wife to Bernard 1, had set out an hour earlier, knowing herself to be slower than the rest of us. In fact, she had set out with Bernard 2 and his wife, who had dropped behind and been overtaken in Bedoin.

A last "à toute à l'heure" and we set off one by one, each for himself. Why this? Quite simply, if you set off with another rider either he accommodates to your pace or you to his, and at some point one of you realises that he has been either straining to keep up or riding below his optimum level. Either way it's a possibly critical waste of energy, and can cost you the climb. So we all set out alone, one by one - with the exception, that is, of Bernard 2 and Bernardette, who stuck together and proved the rule.

I managed perhaps two hundred metres before I had to drop onto my bottom chain-ring, at which point the chain decided to come off - it's common enough on 3-chainring bikes. I stopped to fix it, and lost sight of everyone else as they trogged off round the first bend. Once I had the chain back on, I swapped my crash-hat and bandanna for my baseball cap - the climb is slow and steady, and helmets get infernally hot. The cap keeps off some of the sun, and is much cooler. It's symbolic, anyway: I pinched it from my daughter, and I've worn it on every big climb and long-distance outing that I've done.

Off again. After about 100 metres I realised that I was hurrying to catch up, and deliberately slowed down. But I went past Bernard 2 and his wife, and then Jean-Pierre, whose horrible style meant that his saddle was abrading the skin off his backside. The road entered the forest, and the real work began.

Mont Ventoux is 1909 metres high (or 1912 if you read a different postcard). The climb begins at 300 metres, and from there up to 1400 metres is through forest. At 1400 metres there is a seasonal chalet-restaurant called Chalet Reynard, and above that the slopes are bare limestone, solid and scree, for the last 500 metres of the climb. The usual comparison for this section is with the face of the moon.

But I was a long way from Chalet Reynard, and by no means sure of getting there. The forest was not high and provided little shade. It cut out what wind there was, too, and the temperature was around 28°C. I was outputting around 150 watts to the road which, bikes being about 16% efficient, meant that I was burning around 900 watts to do so: of this, 750 remaining watts were going to heat me up. Pretty soon, the sweat was pouring; and there were 15 km to go before Chalet Reynard and the hope of a cooling breeze.

The forest was pleasant enough to look at. It was all fresh springtime growth, and the smell of resin was wonderful. In fact, smell was one of the strongest factors of this holiday: the smell of fennel and broom baking in the sun, that of basil and rosemary - all the little jars in the kitchen, really, but with an intensity I had never experienced before. But the broom (genet), smelling like warm honey, was the strongest.

Not too far into the forest, and I saw the first "coup de fouet" tube lying discarded on the verge. A "coup de fouet" is usually maltodextrose gel with lots of mineral salts and a bunch of herbal extracts added which either help, or at least do no harm, according to your belief. My faith is in the maltodextrose and the salts. The aim of the coup de fouet (stroke of the whip) is to provide sudden energy via a stomach that is no longer capable of absorbing solid food - this happens when you are nearing the end of your reserves and the body is beginning to close down non-essential centres. Finding such a tube on the first couple of klicks was mildly surprising, and I very much doubt if the rider made it to the top. Or maybe he just didn't know how to use the things, or just liked the taste. Anyway, at this point I realised that I hadn't packed any.

A little further up, and I came to a spruce little sign reading "9% climb for 1 kilometre". The sweat really started to pour now, to the extent that I could blow half-a-dozen fresh drops of it off the end of my nose with every breath. It began to pool in the bottoms of my spectacle lenses, and trickle from there down my cheeks; it got into my eyes, and stung. Wiping it away with a sweaty finger merely wiped it further in.

I began to calculate how many hours of this lay ahead: about 12 km to Chalet-Reynard at 7 kph: a bit under 2 hours. Oh brother... But that first 9% klick seemed to be awfully long, and they didn't tell me when it was over. Presently, though, my speed climbed again, and I reckoned it was past.

Bugs. Bugs can fly *fast* - much faster than I could pedal. Sweating like a pig and dressed in yellow to boot, I soon became lunch on the hoof. They had a way of hovering in front of your mouth so that every inhalation carried the risk of a bristly appetizer, yet breathing through clenched teeth was not an option. I developed the technique of blowing out the last modicum of used air a little harder in order to shift them, before drawing in the next gasp. It worked, most of the time.

Water. I cycle with two bottles, one of water so full of fructose/glucose/replacement-salts mix it's practically a jelly, and the other of plain water. The former keeps me going, the latter rinses the former out of my mouth and off my hands, and also serves to soak the baseball cap on occasion. (It's not a good idea to get mixed up.) About halfway up through the forest and the sugary mix was down by three-quarters and the plain by about two-thirds when a car overtook me and came to a stop. It was Valérie, the sig. other of René, with supplies. I drank down the rest of the sugar, poured the plain over my head, and replenished. It was wonderful: she had not only insulating bags but Bernard 1's carboard fridge on board, and the water was wonderfully cool. Without, I doubt I would have made it.

She disappeared up the road, and I went on.

A little further up and I overtook Solange, sunny as ever. (It's what her name means, I think: Angel of the Sun. Either that or you can derive it from the German, in which case it means "so long". I go with the angel.) She is definitely not a long-distance rider - her usual distance is around 60 km - and she was finding it very heavy, but had no intention of giving up. "I'll walk if I have to," she said. I offered, against common sense, to stick with her a bit, but she told me to get on, so after making sure she had everything she needed, I did.

Nothing much happened for the next hour or so. I drank from time to time, pedalled steadily, and occasionally wondered when the cramp would strike. I switched between sitting down and standing from time to time: if anything will show incipient cramp, this is it. Sure enough, at about 1000 metres, the gracilis muscle in my right thigh began to complain. I sat down, shifted the bulk of the effort to the other leg for a while, and drank a great draught of my sugar mix. The pain disappeared. As it turned out, that was the only hint of cramp I had for the entire week.

Nothing much continued to happen until suddenly I rounded a bend, the slope lessened, and Chalet-Reynard was in front of me.

All of a sudden there were lots of cyclists. Chalet-Reynard is where the easy route, the one starting at Sault, joins the Bédoin route for the final climb. Whereas on the hard climb I had been overtaken by maybe six riders in all, now they were coming past about two per minute - young guys for the most, but a few leathery old blighters like myself, and some of them going like the clappers. I began overtaking quite a few, too, which was pleasant.

Just past Chalet-Reynard there is another signpost. It reads "Mt. Ventoux 1909m, Géant de Provence, 6km. 7,1% sur 1 km. Alt. 1441 m." This is about 300 metres higher than I had ever been and thus worth a photo (although I was certain now that I was going to the top) so I stopped and fished out the camera. As I sighted it, a voice behind me said, in Dutch that I managed to understand, "too much for you, huh?" and a much younger rider with a Dutch flag flying from the back of his saddle came past. That was the only adverse comment I heard on the entire climb.

I went on. There was that long-awaited breeze now, nothing too much but, wonder of wonders, it was helping instead of opposing. I hardly noticed the next few klicks: I was too amazed that I was actually succeeding, that I wasn't hurting too much, that I was breathing easily and that even the bugs were gone. And then there was the view...

Penultimate reward: I come round a bend and see a yellow and green shirt just like mine in the distance. It slowly grows into Bernard 1, stopped for a piddle and a photo. Since in spite of the litres I've been drinking I haven't needed to pee for the last five hours, I reckon that his need is no greater than mine, but I would never suggest it. I ask if all is OK, then go on past.

A couple of loops below the final kilometre, and I pass the monument to Tom Simpson, the great English rider who died on the Ventoux during the 1967 Tour de France, pushed by amphetamines to exceed the limits of his endurance. Nearly 40 years on, passing riders still stop to place tributes at the foot of the stele - water bottles, maps, routing sheets, cards, or even just stones, in the spirit of a cairn. I give him a nod, but I can't stop now.

Into the final leg. The slope increases here, or else it's more sheltered from the helping wind, or else the proximity of the top makes you want to go faster: no-one can really say, but this leg is certainly the hardest of the lot. At the bottom of it I meet another Dutch rider, this one on a mountain bike, stalled. I hover a bit and ask if he's OK, if he needs a drink. He says he's just very tired, but he tags along behind when I get going again, and we exchange a few inarticulate words on the last climb.

Two hundred metres to go, and I hear a cheer from above me. I glance up, and see that the parapet is lined with Armand, Roland, René, Augustin and the crew of our two support cars, and they are all clapping and cheering and calling my name. Has this ever happened to you? It is one of the greatest feelings in the world, and I feel a sudden great love for all of them. Strength, too: my friendly Dutchman is suddenly ten metres behind, and I feel no pain at all. I round the final bend and up the final, horribly steep, ramp onto the car park, and into their arms. Handshakes, back slapped, more cheers. The Dutchman cruises to a halt beside me and sticks out a hand. "Thank you", he says, and we congratulate each other.

It's done. On the third day I have risen from the dead and ascended into heaven.

Another fifteen minutes, and Bernard 1 appears at the bottom of the final klick. We cheer him home, and Jean-Pierre half an hour later. And half an hour after that, our resolute Angel of the Sun appears. She stops for a breather at the bottom of the last climb and then, to our cheers even though she is too far away to hear, she gets going again. She makes the slope painfully, very slowly, but steadily. When she gets within earshot, she looks up and waves, and we cheer all the louder. The 500+ other people present look rather bemused, but some of them have a look and cheer too. She comes up the final ramp and onto the flat to hugs, kisses, congratulations and cold drinks.

Of Bernard 2 and his wife we see no more that afternoon. The support teams dole out jackets (it's cold up there when the clouds cover the sun) and we mill around for another hour, perhaps, taking photos, eating, drinking and talking away twenty to the dozen. We can't stop grinning. I pick up a chunk of rock for Gill. Then it's off downhill again, an eye-watering descent that takes a mere 20 minutes, with the bugs hitting us like bullets. We have a picnic in Malaucène, then split up for the rest of the day. Four of us eat enormous ice-creams, then wonder of wonders, Augustin and I find the energy to race the final eight kilometres home. I screw up my gears on the last 100 metres climb to the hotel and he wins by a length.

And that is that.

Well, nearly. Two days later we rode up by the Sault route to Chalet-Reynard to watch Lance Armstrong lose a time-trial; and if rest of the road hadn't been closed we would have been up top again.

I'll definitely be doing this again, and other similar peaks: there are great slopes in the Massif Central, and the high cols of the Pyrenees, but I don't know if I'll ever again feel the way I felt when that cheer came down the mountain.

I hope I do. That kind of thing is addictive.

[Journey's end - QED]

![]()

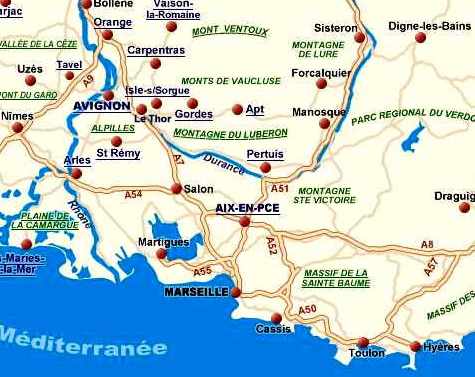

[a] More information on this area of great natural beauty may be found at the Provence Heritage & Nature site http://www.provenceguide.com/gbcdt/patrimoine.asp. For readers who are not acquainted with the geography, it may be located on the following map:

![]()

[1] What do the percentages mean? A 5% slope means that in 100 metres you

rise five metres: 5/100 = 5%. This doesn't seem like much, especially to

pedestrians, but it means that for a bike/rider combination weighing 85kg, a

force of 4 kg - roughly the weight of a gallon of water - is pressing you

back. When you hit a 10% slope, this rises to about 9 kg. It's not much

in the way of weight-lifting, but maintaining that force *and* pushing the

bike at any kind of speed for three hours is quite taxing.

![]()

Biodata

John Ewing is a software engineer in his mid-fifties. Diagnosed with

diabetes in the early 1990s, he took up road cycling in 1997 as a means of

keeping fit. He lives in Alsace, France.

We would remind readers also of John's poem about cycling published in the last issue of Nurturing Potential and viewable at http://www.nurturingpotential.net/Issue12/Verse12b.htm