Groups and Groupwork

WHAT

IS GROUP THERAPY?

The basic difference between "normal" (one-to-one) therapy and group therapy is almost too obvious to require explanation. In standard therapy or psychotherapy, the patient - or client - meets with just one person: the therapist. In group therapy or psychotherapy, participants meet as a group that normally (though not necessarily) has one or two qualified therapists (usually referred to as the group leader/s or facilitator/s) present to control the session.

|

"If you wish a group therapy practice, you must make it happen, and part of that is being flexible and creative but never sacrificing ethics." (Dr. Scott Simon Fehr) |

How does it work?

Group therapy focuses on interpersonal interactions and emotional difficulties, and consequently there are a number of situations that are more appropriately handled in a group context than might be handled in a standard one-to-one psychotherapy session. Foremost amongst these, perhaps, are situations involving relationships.

Members of the group share with others personal issues which they are facing. Participants can talk about events they were involved in since the previous session, their responses to these events, and problems they had faced. Participants can also share their feelings and thoughts about what happened in previous sessions, and relate to issues raised by other members. Other participants can respond to this material, give feedback, offer encouragement, volunteer support or criticism, or share their own thoughts and feelings.

Subjects for discussion are not usually determined by the leader but rise spontaneously from the group. As groups mature, and participants begin to feel more comfortable with other members, a synergy develops and there is bonding between participants who, in course of time, feel they are not alone, that their problems are shared, and that there are even others who are experiencing the same types of situation. The group then becomes a source of support and strength in times of stress for the participants. The feedback they get from others helps to make them aware of inappropriate, disruptive, aggressive, or maladaptive patterns of behaviour.

|

"The deepest reason why patients... can reinforce each other's normal reactions and wear down and correct each others neurotic reactions, is that collectively they constitute the very norm from which, individually, they deviate." (Foulkes, 1949) |

There are many different motivations associated with participation in group therapy. At one extreme are the people with severe emotional difficulties and disorders such as anxiety and depression. Some groups are, indeed, targeted towards a specific problem area. Examples of such groups would be those devoted to victims of cancer, or people dealing with bereavement; sexually abused women have formed self-help therapy groups; the Alcoholic Anonymous organisation group meetings might be included in this category. But at the other extreme we find groups devoted to people who want to develop their interpersonal skills; the T-Group comes into this category.

Group therapy is ideally suited to people who are trying to deal with relationship issues such as intimacy, trust and self-esteem. Group interactions help the participants to identify, get feedback, and change the patterns that are sabotaging the relations. The great advantage of group therapy is that you are working on these patterns in the "here and now"; the group situation is similar to the real situation and frequently the people you meet in the group represent others in your past or current life with whom you have difficulty. In group therapy you have the opportunity to work through these situations; and, importantly, you are doing so in a safe and secure environment.

What are the conditions of group membership?

Typically, groups will comprise between 8 to 12 members. Too many members makes it impossible to create a therapeutic atmosphere and have enough time for each member to work personally. Usually each session will last from an hour and a half to three hours, but workshops and marathon groups will be of much longer duration. The frequency can be once or twice a week. How long a group survives depends on many factors such as the severity of the problems and the targets sought. It can be from a few months to a few years. It usually takes about four to six months before the group reaches maximum effectiveness.

The participant in the group is expected to be present each week and come on time. It is required that the information brought up by members of the group and their names be kept confidential by all the group members. In some groups, the participant is asked to commit for a specified length of time at the beginning of the group. A typical commitment is between 3 and 6 months. Group participants are not required to talk, or reveal intimate details of themselves. Clearly, however, the more they participate and talk frankly and openly about themselves, their feelings, their thoughts, the more they will gain from the experience.

How do different groups differ from each other?

The major differences in therapy groups may be divided into categories such as their size, the purpose for which they were created, their projected outcome, the techniques they use, the way they are facilitated, and any specified membership restrictions such as age, gender or condition.

Generally the considerations that govern the structure of a therapy group will not be dissimilar from those that apply to other types of group. These were fairly extensively described and defined in our previous issue and may be reviewed at http://www.nurturingpotential.net/Issue7/Leader7.htm, in the section What are the principal characteristics of groups?

|

". . . a functioning group could be seen as a communication process in which competing discourses come into conflict, with the aim to free each group member from being stuck in ones own discourse, ones own experience of the self and the world, and opens up the possibility of connecting with other discourses, other ways of being and experiencing to which one did not have previous access" (Farhad Dalal, 1998) |

What techniques are used?

The techniques used in group therapy can be verbal, expressive, dramatic, pacific, confrontational. and so on, depending on the discipline upon which the group is based.. Approaches can vary from psychoanalytic to cognitive-behavioural, Gestalt, Encounter. Groups may vary from classic psychotherapy groups, where process is emphasized, to psycho-educational, which are closer to an educational class and focus on such common areas of concern as relationships, stress-management, and anger.. Each approach has its advantages and drawbacks, and participants may be advised to consult an expert to establish which techniques best match their personality.

There are, however, certain general techniques and methods from which all group members will benefit and to which all should aspire.

One of these is Active Listening. This comprises maintaining eye contact with the speaker; giving undivided attention; non-intervention during the speaker's "time"; ensuring that you have clearly understood the message. And active listening is required whether it is to a suggestion by the facilitator, a statement by a single member of the group, participation in a small group, or participation in a large group.

Role Play/Psychodrama is another very useful and popularly employed technique. This develops interpersonal skills because it is based upon real life situations. It provides a dynamic way of exploring problems and enables group members to enjoy active participation. It is also beneficial in providing a risk-free environment for participants to make mistakes without fear of failure or embarrassment.

Brainstorming is a quick and participative method of producing a large number of ideas quickly, usually facilitated with the aid of a black/whiteboard or flipchart, whereby the facilitator invites members to call out as many suggestions as possible and writes them down without any interruption for analysis of the ideas or their relevance. This comes at a later stage and much useful material is produced by the subsequent consideration of the suggestions.

How is it facilitated?

A minimum of intervention is required of group facilitators. Each member of the group, in effect, is a therapist as well as a patient, a counsellor as well as a client. The group unit is the individual, but each individual is an integral part of the entire network of group relations. This network includes the facilitator whose primary function is one of protection. Facilitators are there to provide expertise, knowledge, and a safety net . . . but only when it is demanded or when their experience suggests that it is required. Indeed the facilitator's success may be measured by the effectiveness with which he or she has been able "to wean the group from this need for authoritative guidance..." (Foulkes, 1964)

"The leader as a facilitator of interpersonal transactions is neither passive nor claims the centre state but will be both observer and reflector of what is going on in the group . . . The leader also models helpful group behaviour to the members . . . The leader models respectful attention, giving full weight to what is being disclosed." (Bernard Ratigan and Mark Aveline)

Participants, including facilitators, are expected to develop the ability to communicate and listen to each other in a non-judgemental, non-directive, and non-manipulative way. Conflicts which develop between individuals are resolved by the concerted action of the entire group, including the facilitator, without overt or direct intervention, but by what has been termed "a free-floating communication by the group analytic attitude" (Foulkes & Anthony, 1965).

Dr. Scott Simon Fehr has made an interesting point about the importance of clinicians to experience the group dynamic at first hand. This is advisable for any potential leader or group facilitator. "I also feel it is vitally important that a clinician go into group therapy as a patient before beginning to implement group therapy into his or her practice. The general training of group psychotherapists . . . is not sufficient to teach group dynamics in an academic setting nor is internship or practicum sites sufficient in creating truly effective group therapists. Only experience on "both sides of the desk" and life experience in general, in my personal opinion, creates a truly effective group therapist. Personal experience in group therapy and working through ones own interpersonal issues as a member, is perhaps the best route to go if you wish to truly learn about yourself and experience the process of group psychotherapy. There is an old psychoanalytic statement, which I completely believe, stating, "We can only take a patient as far as we ourselves have gone." In order for you to sell the process and you must sell the process, you too must wholeheartedly believe in it and one of the the best ways to do that is to experience it firsthand as a patient."

|

"It is always more useful to have two leaders, preferably of differing genders. Besides providing support for each other, two leaders can adopt varying degrees of involvement and detachment; for example, if one leader is under attack by the group, the co-leader can help the group to examine what they are doing. Having a man and a woman leader often stimulates the exploration of sexual and parental conflicts" (Bernard Ratigan and Mark Aveline) |

The Johari Window

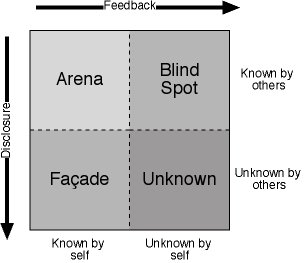

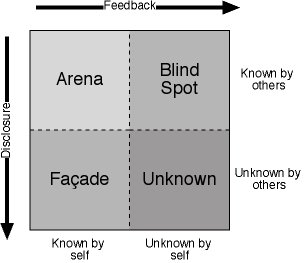

The name derives from a combination of the forenames of its two inventors, Joe Luft and Harry Ingham. It consists of four panes and forms a very useful facilitative model when used in group therapy. The four panes comprise the things about ourselves that exist and may be hidden from ourselves or from others, hidden from ourselves though revealed to others, revealed to ourselves while hidden from others, or openly admitted to ourselves and revealed to others.

The last of these is what is in the public arena. It is knowledge that is shared with others and is the basis of our interaction with others. Within this pane we enjoy the most effective communication.

The facade, or mask as it is sometimes called, is that part of our personality that is known to us, but which we hide from others. It is the area of the "games people play". The larger the area of this pane, the less will be the possibility of developing meaningful and trusting relationships with others.

The Blind Spot might be termed the Ostrich Factor. Our head is buried in the sand. We see, we know nothing, but others may see, may know. We are exposing our weaknesses and making ourselves vulnerable to the manipulation of others, but we are unaware of this.

In the Unknown pane ("Here be dragons") we hide both from ourselves and others much of the potential of which we are capable. Here lurk our hidden resources.

In

the context of group therapy this ties in with the four major activities that

are deployed within the group. These are: disclosure, feedback,

acceptance, and risk taking. The size of the Arena may be expanded, at the

expense of the other panes, by self-disclosure, that is by sharing information

about the real you with others. This will also increase their knowledge

about you and thus their ability to provide more meaningful feedback. The

feedback will then provide honest and open information about you from the people

who are able to witness your behaviour and your performance. This will

help to reduce blind spots.

.![]()

![]()

References:

Foulkes, S. (1949). Introduction to Group-Analytic Psychotherapy., London: William Heinemann.

Foulkes, S. (1964). Therapeutic Group Analysis., New York: Int. Univ. Press.

F. Dalal (1998) - Quoted by Werner Knauss, The Group as the Therapist, in a paper given to the American Group Psychotherapy Association, Boston, Mass, February 2001.

Foulkes, S., & Anthony, E. (1965). Group Psychotherapy: The Psychoanalytic Approach. 2nd ed., Baltimore: Penguin Books

Bernard Ratigan and Mark Aveline, Interpersonal Group Therapy (in Group Therapy in Britain, Open University Press, 1988).

Dr, Scott Simon Fehr, Developing a Group Psychotherapy Practice, in an article submitted to the Group-psychotherapy.com website.