LANGUAGE - A Nurturing Potential series

Part IV -AMBIGUITY

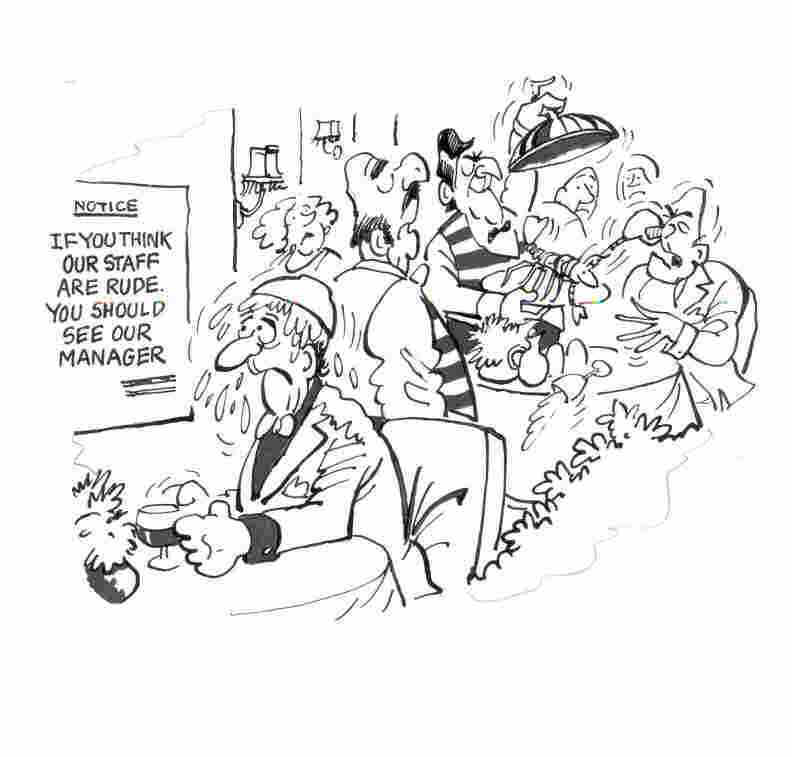

The disastrous charge of the Light Brigade at Balaclava in the Crimean War was made because of a carelessly worded order to "charge for the guns" - meaning that some British guns which were in an exposed position should be hauled out of reach of the enemy, not that the Russian positions should be charged. (1)

[Illustration by Albert Saunders from An ABC of NLP, ASPEN London, 1992]

The second edition of An ABC of NLP [1998] defines Ambiguity as "The experience of encountering sentences which have more than one meaning. For example: I must leave you to discover an example, or We agree with striking workers." Reference is also made to the transformational model of language. a linguistic method of analysis first suggested by Zellig S. Harris and developed by his pupil Noam Chomsky, wherein two levels of structure are identified in language: deep structure and surface structure. Surface structure is the means by which a statement is presented to the world; deep structure is the unconscious level containing content, context and relationships and meaning has to be deduced using the experience of our culture.

Thus the difficulty in avoiding ambiguity. A useful working tip is: never assume that because a thought, a statement, or a sentence is clear to you, it must necessarily be clear to others.

A remarkable work, published first in 1930, and reprinted and revised on innumerable occasions since then, was Seven Types of Ambiguity,[2] a book that seems as fresh today as when it was first published. Empson defines ambiguity as any verbal nuance, however slight, which gives room for alternative reactions to the same piece of language. He then proceeds to consider a series of ambiguities and "to arrange them in order of increasing distance from simple statement and logical exposition."

The seven types "intended as stages of advancing logical disorder" are illustrated by a number of poetic examples. Thus, the first ambiguity "occurs when two or more meanings all add to the single meaning of the author:

Cupid is winged and doth range;

Her country so my love doth change.

But change she earth, or change she sky

Yet I will love her till I die.

"Change" may mean "move to another" or "alter the one you have got", and "earth" may be "the lady's private world, or the poet's, or that of mankind at large."

Another type of ambiguity "occurs when two ideas which are connected only by being both relevant in the context, can be given in one word simultaneously." A further type "occurs when two or more meanings of a statement do not agree among themselves, but combine to make clear a more complicated state of mind in the author."

Of the next type of ambiguity, Empson draws the conclusion: "Ambiguities of this sort may profitably be divided into those which, once understood, remain an intelligible unit in the mind, those in which the pleasure belongs to the act of working out and understanding . . . and those in which the ambiguity works best if it is never discovered. To illustrate this he subjects Shakespeare's 18th Sonnet "But wherefore do not you a mightier way," to a searching analysis of the equivocal words and the ambiguous grammar.

The fifth type of ambiguity occurs where there is a "simile which applies to nothing explicitly, but lies half way between two things when the author is moving from one to the other. Shakespeare continually does it."

Our natures do pursue

Like rats that ravin down their proper bane

A thirsty evil, and when we drink we die.

The ambiguity lies with the use of the word "proper" to mean a poison suitable for rates, but also having an irrelevant suggestion of "right and natural".

Another type of ambiguity "occurs when a statement says nothing by tautology, by contradiction, or by irrelevant statements, so that the reader is forced to invent statements of his own." An example is taken from Max Beerbohm's Zuleika Dobson that "she was not strictly beautiful." Empson comments: "Do not suppose that she was anything so commonplace as [merely beautiful]; do not suppose that you can easily imagine what she was like, or that she was, probably, the rather out-of-the-way type that you particularly admire".

Of the seventh type, Empson states: "the most ambiguous that can be conceived, occurs when the two meanings of the word, the two values of the ambiguity . . . are the two opposite meanings defined by the context, so that the total effect is to show a fundamental division in the writer's mind." Thus in Macbeth:

Come what may,

Time, and the hour, runs through the roughest day.

Here are some examples, taken from The Reader Over Your Shoulder (1) which you might try to fit into Empson's categories. Some actually fit into several simultaneously.

[From a newspaper story} "Ex-Sergt. Oliver Brooks, VC, hero of Loos, who has died at Windsor, aged 51, was decorated by King George V, who was in bed in a train, following the accident when he fell from his horse in France."

"I admire the man who is man enough to go up to a man whom he sees bullying a child or a weaker man and tell him, as man to man, that he must lay off."

[From a pamphlet by Professsor Denis Saurat, Director of the Institut Francais in London: "In the animal races those in which the female bears in pain give the greater care to their young, and those races in which birth is painless show, as a rule, no affection for their offspring."

![]()

Some comments

There are three types of ambiguity:

linguistic ambiguity when one or more words has multiple possible meanings;.

logical ambiguity when there is an illogical concept;

structural ambiguity when the organization of the text leaves an uncertainty.

From: www.textsandtech.org

William Empson ( 1947) distinguished a series of different types of ambiguity, though Empson, writing about poetry, identified some types not relevant to disputes. (A "fortunate confusion" is a concept of ambiguity attributable, in the context of an agreement, only to someone who hopes to make a living from it.) Of Empson's fist, these seem applicable to disputes: "when a detail is effective several ways at once"; "simultaneous unconnected meanings"; "a contradictory or irrelevant statement, forcing the reader to invent interpretation"; and "full contradiction, marking a division in the author's mind." All of these are consistent with a condition not normally present in poetry—the opposing purposes of plural authors. Varying circumstances can cause negotiators to accept any of these types of ambiguity; study might reveal that certain forms best fit particular negotiating situations, but at present all I am prepared to say is that deliberate ambiguity in an agreement has the same origin and overall purpose no matter which of these forms it may take.

From: Christopher Honeyman, In Defence of Ambiguity [in negotiations]: www.convenor.com

Two different types of ambiguity can be distinguished on the basis of what is causing it: lexical ambiguity is the type of ambiguity that arises when a word has multiple meanings. The word bank is often cited as an instance of lexical ambiguity; and structural ambiguity that arises from the fact that two or more different syntactic structures can be assigned to one string of words. The expression old men and women is structurally ambiguous because it has the following two structural analyses:

(i) old [men

and women]

(ii) [old men] and women

From: www2.let.uu.nl

![]()

Footnotes

(1) The Reader Over Your Shoulder, by Robert Graves and Alan Hodge, Jonathan Cape 1943, p.81

[2] Seven Types of Ambiguity, by William Empson, Chatto & Windus, First Edition 1930.

Additional Bibliography

Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic Structures. The Hague: Mouton.

Frazier, L. (1987). Sentence processing: a tutorial review. In M. Coltheart, Ed., Attention and Performance XII: The Psychology of Reading. London: Erlbaum.

Simpson, G. (1984). Lexical ambiguity and its role in models of word recognition. Psychological Bulletin 96:316-340.

Zwicky, A., and J. Sadock. (1975). Ambiguity tests and how to fail them. In J. Kimball, Ed., Syntax and Semantics, vol. 4. New York: Academic Press.