Let Him Have It!

by Joe Sinclair

Some readers will recall how the phrase at the head of this article resulted in the execution of a young man and the successful British movie that resulted from that event. The court case that preceded the execution, and the film that followed it, devolved on the ambiguity of that phrase. Did the friend who urged the wielder of the pistol intend that he "surrender the weapon" or (in the vernacular) "fire the weapon". Either meaning would be acceptable in its written form; the actual meaning would have depended upon the way in which it was spoken and none of the jurors, of course, had been present to hear it spoken. Of the only two who had, one was now dead, and the other, who had actually fired the weapon, was too young to be sentenced. The young man who received the death sentence, the one who had uttered the ambiguous instruction, had been judged "mentally substandard" and unfit for military service, but fit enough to be executed.

This is a somewhat extreme example of structural ambiguity. It is ambiguity that arises from the interpretation of a phrase. It is distinguished from lexical ambiguity which is ambiguity of a single word.

Lexical ambiguity can be of different types. If it is based on a homonym, it consists of a word spelled exactly as another, but with a different meaning. If it is based on a homophone, it consists of a word spelled differently from another but pronounced similarly. If a ticket left on your car windscreen is headed "Parking Fine", it is unlikely that the word "fine" is intended as a compliment on your parking. A fisherman at the bank may be depositing money or casting for perch. Either interpretation of "bank" is equally valid. These (fine and bank) are homonyms. "There was a long queue (cue?) at the billiard hall" might be understood in context, but either meaning would sound the same. "Is that a boy (buoy) I see out there?" Hearing the question without being aware of the circumstances could result in an unwarranted request for a lifeboat. These are examples of homophones.

I recall a rather silly piece of verse from many decades ago.

"I love thee well

"I do not know how else to tell

"I love thee well."

Then fairer belle he met and so;

"I love thee?

"Well, I do not know."

This is an example of grammatical (or syntactical) ambiguity. It is perfectly understandable when read and proper note is taken of the grammar, the syntax, and the punctuation. Rather more ambiguous when one listens to it being spoken. Another example is "I found him a good worker". Did I find that he was a good worker, or did I find a good worker for him? Possibly the best-known example of syntactical ambiguity is attributed to Groucho Marx: "Last night I shot an elephant in my pyjamas. How he got into my pyjamas, I'll never know."

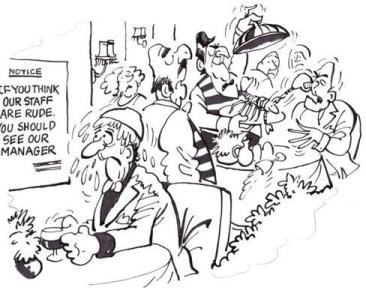

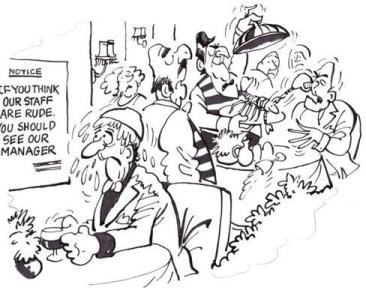

For those who enjoy the use of arcane language, it may be noted that grammatical ambiguity is also known by the name amphibology (or sometimes simply amphilogy). And examples are often quoted humorously in newspapers and magazines . . . or, nowadays, in blogs and exchanges on social networking sites. Such notices as, for example, the environmental injunction to "save soap and waste paper" that is simultaneously concerned and pernicious.

[Illustration by Albert Saunders from An ABC of NLP, ASPEN London, 1992]

Metonymy is another example of the use of a word in a different sense from that originally intended, or the substitution of a word denoting part of a thing for the thing itself. "A nice set of wheels", for "a nice car"; or "the pen is mightier than the sword" for "the written word is more powerful than a show of force"; or "lend a hand" for "render help or assistance".

Seven Types of Ambiguity

A remarkable work, published first in 1930, and reprinted and revised on innumerable occasions since then, was William Empson's Seven Types of Ambiguity, a book that seems as fresh today as when it was first published. Empson defines ambiguity as any verbal nuance, however slight, which gives room for alternative reactions to the same piece of language. He then proceeds to consider a series of ambiguities and "to arrange them in order of increasing distance from simple statement and logical exposition."

The seven types "intended as stages of advancing logical disorder" are illustrated by a number of poetic examples. Thus, the first ambiguity "occurs when two or more meanings all add to the single meaning of the author:

Cupid is winged and doth range;

Her country so my love doth change.

But change she earth, or change she sky

Yet I will love her till I die.

"Change" may mean "move to another" or "alter the one you have got", and "earth" may be "the lady's private world, or the poet's, or that of mankind at large."

Another type of ambiguity "occurs when two ideas which are connected only by being both relevant in the context, can be given in one word simultaneously." A further type "occurs when two or more meanings of a statement do not agree among themselves, but combine to make clear a more complicated state of mind in the author."

Of the next type of ambiguity, Empson draws the conclusion: "Ambiguities of this sort may profitably be divided into those which, once understood, remain an intelligible unit in the mind, those in which the pleasure belongs to the act of working out and understanding . . . and those in which the ambiguity works best if it is never discovered. To illustrate this he subjects Shakespeare's 18th Sonnet "But wherefore do not you a mightier way," to a searching analysis of the equivocal words and the ambiguous grammar.

The fifth type of ambiguity occurs where there is a "simile which applies to nothing explicitly, but lies half way between two things when the author is moving from one to the other. Shakespeare continually does it."

Our natures do pursue

Like rats that ravin down their proper bane

A thirsty evil, and when we drink we die.

The ambiguity lies with the use of the word "proper" to mean a poison suitable for rats, but also having an irrelevant suggestion of "right and natural".

Another type of ambiguity "occurs when a statement says nothing by tautology, by contradiction, or by irrelevant statements, so that the reader is forced to invent statements of his own." An example is taken from Max Beerbohm's Zuleika Dobson that "she was not strictly beautiful." Empson comments: "Do not suppose that she was anything so commonplace as [merely beautiful]; do not suppose that you can easily imagine what she was like, or that she was, probably, the rather out-of-the-way type that you particularly admire".

Of the seventh type, Empson states: "the most ambiguous that can be conceived, occurs when the two meanings of the word, the two values of the ambiguity . . . are the two opposite meanings defined by the context, so that the total effect is to show a fundamental division in the writer's mind." Thus in Macbeth:

Come what may,

Time, and the hour, runs through the roughest day.

"The crisis of action or of decision will arrive whatever happens."

Moving on from language

So far we have been considering ambiguity in the context of language and, in the case of Empson's work, it was particularly devoted to poetry, although it ranged far beyond that. But there is a much greater body of work that relates ambiguity to philosophy, specifically logic. Ambiguity also looms very large in works of religion and politics. This is too vast a subject to be treated other than superficially in this article, and I shall return to it in future issues of Nurturing Potential. Amongst the works I shall be considering will be Simone de Beauvoir's Ethics of Ambiguity, Robert McKim's Religious Ambiguity and Religious Diversity, and William E. Connolly's Politics and Ambiguity, as well as calling upon an old friend of ours (and the pages of Nurturing Potential) for some apposite commentary - namely Stuart Chase.

For now, let us return to the somewhat light-hearted way in which we began this article with a few examples of literary ambiguity.

1. Where was the Magna Carta signed? (At the bottom of the page)

2. "I can assure you no person would be better for this job." (An answer to a request for a reference)

3. For sale, antique desk suitable for lady with thick legs and large drawers.

4. (Possibly apocryphal) It is said that when Gandhi was asked what he thought of Western civilization he replied: "It might be a good idea".

No apologies are offered for the somewhat dated nature of these examples and the probability that you have read them before. And you could perhaps discover at least a couple of ambiguities in this lack of an apology.