Models for

Health Beliefs

A Nurturing Potential report

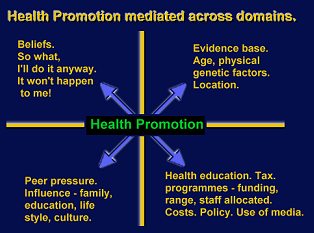

[Map courtesy of Hodges

Health Career Model]

There are a number of psychological models, designed to

predict and explain health behaviours and, in several cases, to propose

prescriptions to arrest and replace those behaviours with more appropriately

healthy alternatives.

We discussed one such model at great length in the second

issue of our magazine, in 2002 (http://www.conts.com/NPHome.html)

where we did not merely describe the prescriptions for identifying the various

stages of health behaviour, but also provided an article describing the

processes by which the authors of the Model intended it to be utilised.

The Transtheoretical Model of Change

(otherwise known as Stages of Change model)

This model, which has been applied to many areas outside that

of health, was originally promoted as a means of identifying and replacing

addictive behaviour, particularly drug and nicotine abuse.

The Health Belief Model

This model dates back to the 1950s

and was initially developed in response

to the failure of a free tuberculosis (TB) health screening

program in the United States. Since then it has been adapted to explore a

variety of long and short-term health behaviours, including sexual risk and the

transmission of HIV/AIDS.

The Model has been applied to a range of

health behaviours and classes of subject. Preventive health behaviours,

for example, would include diet and exercising to promote good health;

preventive measures such as vaccination and contraception; risk behaviours,

such as smoking and substance abuse; and clinical use by medical

professionals.

Four perceptions serve as the main

constructs of the model. As illustrated above, these are Perceived

Susceptibility, Perceived Seriousness, Perceived Benefits, Perceived Barriers.

A fifth construct of Self-Efficacy was subsequently added.

In principle, knowing what aspect

of the Health Belief Model patients accept or reject can suggest appropriate

interventions. For example, if a patient is unaware of his or her risk factors

for one or more diseases, attention can be focused on informing them about

personal risk factors. If the patient is aware of the risk, but feels that the

behaviour change is overwhelming or unachievable, the focus can be on helping

them overcome the perceived barriers

Self-efficacy refers to the extent of an individual’s belief in their abilities.

It is based on feelings of self-confidence and control, and is a good predictor

of motivation and behaviour. Recognizing and rewarding the patient for

accomplishing tasks is a useful method of helping to build the esteem that is

the basis of self-efficacy.

Self-Efficacy

This section follows on naturally from the preceding description of the Health

Belief Model to which it was added in an attempt better to explain individual

differences in health behaviours.

The model was

originally developed in order to explain engagement in one-time health-related

behaviours such as being screened for cancer or receiving an immunization.

Eventually, the health belief model was applied to more substantial, long-term

behavioural change such as diet modification, exercise, and smoking.

Developers of the model recognized that confidence in one's ability to effect

change in outcomes (i.e., self-efficacy) was a key component of health behaviour

change, and reflected a person's ability to persist

and to succeed with a task. As an example, self-efficacy directly relates to how

long someone will stick to a workout regimen or a diet. High and low

self-efficacy determine whether or not someone will choose to take on a

challenging task or write it off as impossible.

Self-efficacy affects every area of human endeavour. By

determining the beliefs a person holds regarding his or her power to affect

situations, it strongly influences both the power a person actually has to face

challenges competently and the choices a person is most likely to make. These

effects are particularly apparent, and compelling, with regard to behaviours

affecting health.

Most

people can identify things they would like to change, things they would like to

accomplish and goals they would like to achieve. A person's self-efficacy

will determine how successful they are likely to be in facing these challenges.

Although

we have introduced this subject in connection with the health model to which it

was related, it covers such a vast area of human endeavour that we propose

treating it in a complete article in the next issue of Nurturing Potential.

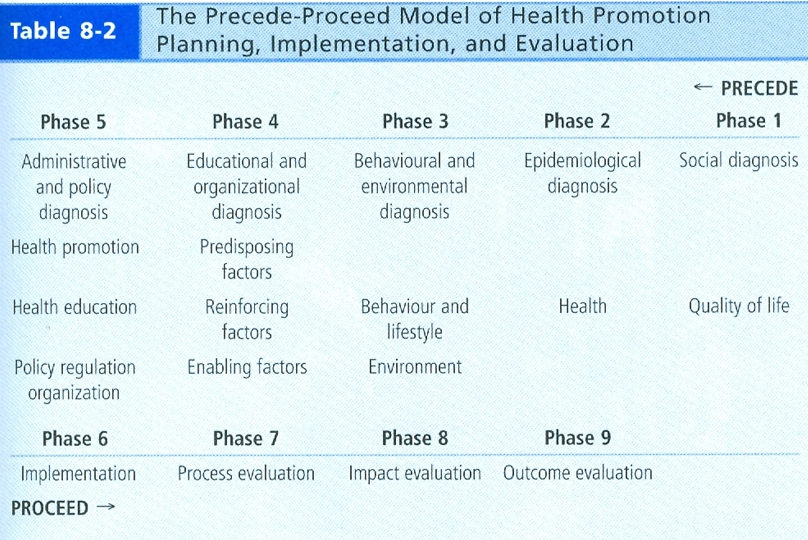

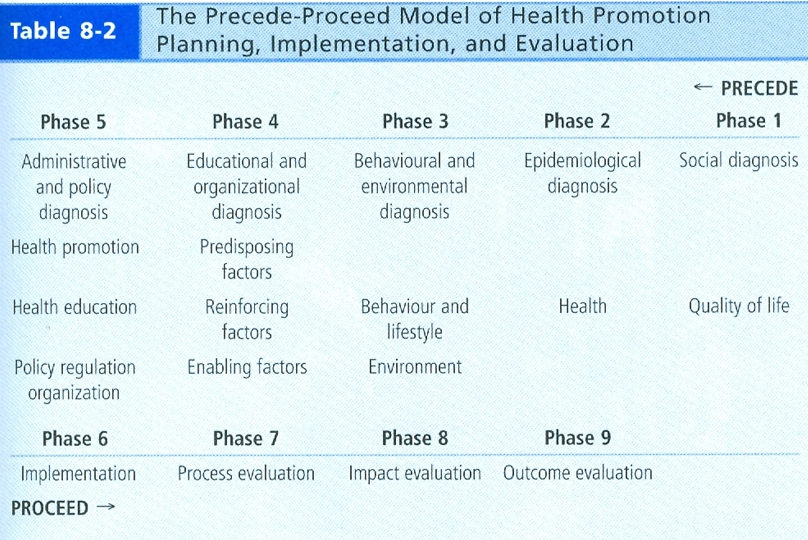

The Precede-Proceed Model

[Source: Green & Kreuter 1991 - adapted by permission by Health Promotion in

Canada]

The Precede-Proceed Model is a theoretical

framework designed to help health promotion professionals to plan, structure and

implement a programme of health promotion. It also enables the evaluation

of existing or developing programmes.

The Precede-Proceed framework for

planning is founded on the disciplines of epidemiology; the social, behavioural,

and educational sciences; and health administration. Throughout the work with

Precede and Proceed, two fundamental propositions are emphasized: (1)

health and health risks are caused by multiple factors and (2) because health

and health risks are determined by multiple factors, efforts to effect

behavioural, environmental, and social change must be multidimensional or

multisectoral, and participatory

The name derives from its two progenitors:

"PRECEDE" is actually an acronym that stands for Predisposing,

Reinforcing, and

Enabling Constructs

in Educational Diagnosis

and Evaluation. It outlines a means for accurately diagnosing and

planning a public health

programme for a targeted community. "PROCEED" is

also an acronym for Policy,

Regulatory, and Organizational

Constructs in Educational

and Environmental

Development. It

facilitates the programmes designed as a result of the

Precede process by guiding the

implementation and evaluation of those Precede

programs. While

Precede

works backward from the desired end result, attained

through the diagnostic process, to the beginning point of

the assessment process,

Proceed

works forward to implement the designed plan and to

evaluate its effectiveness.

The PPM is very much an ecological approach to health promotion. The PPM is

actually quite simple to understand once one realizes that it embodies two key

aspects of intervention: a) planning, and (b) evaluation. The PPM guides the

program planner to think logically about the desired end point and work

"backwards" to achieve that goal. Through community participation, the planning

process is broken down into objectives, step 3 sub-objectives, and step 4

sub-objectives. Conceptually, this approach to health promotion provides context

to the use of theory, with theory being applied at the fourth step. This

observation teaches a vital lesson, namely that programme planning is larger and

is a more comprehensive task compared to the subservient function of theory

selection and application.

Precede was devised in the 1970s, based on the premise that just as a

medical diagnosis precedes a treatment, so should an academic diagnoses precede

an intervention. Proceed was added in 1991 to recognise

environmental factors as determinants of health and health behaviours.

In 2005 the model was revised again to reflect the growing interest in

ecological and participatory approaches.

The Relapse Prevention Model

[Click on thumbnail for full size diagram]

This model calls for the identification of high-risk

situations for relapse and the development of solutions that prevent a

lapse (a single departure from healthy behaviour) from turning into a

relapse (a return to an addictive lifestyle).

A

technique called Relapse Prevention Planning can can make all the difference.

By thinking ahead, and by working out ways to handle the pressures that might

lead you back to your drinking, drug use or gambling, you can approach your new

life with a greater sense of confidence.

Relapse

Prevention Planning is based on the experiences and successes of many people who

have travelled the road to recovery. It recognizes that the road often has many

rough patches, and that to succeed on this road you will need a relapse

prevention plan.

A lifestyle change, however, is not easy to

make or maintain. Some people relapse

several times before new behaviour

becomes a regular part of their

lives. Thus, it is important to

learn about and use relapse

prevention techniques. First

though, it is helpful to understand the

process of relapse.

Relapse Process

At some point after making a

change, for instance stopping

smoking or attending an addiction

control group meeting, the

demands of maintaining it seem to

outweigh the benefits of the change.

We don’t remember that this is

normal. Change involves resistance.

We feel disappointed. We

forget—disappointment is a normal

part of living. We feel deprived, victimized,

resentful, and blame ourselves. We

imagine that our old behaviour would

help us feel better.

These are warning signs for a

"lapse". At this point talking

to a supportive person, or some

other form of distraction or

relaxation could help relieve the

pressure.

Cravings continue and increase.

There are so many reminders of our

old behaviour. People enjoying

cigarettes or alcohol in a movie.

The cynical or demeaning comments of

others. It is so easy to

lapse. If we recognise that

this is a natural reaction and we

have a supportive person or a plan

to distract us, we may succeed in

stopping the lapse from become a

relapse. If we allow the guilt

of our lapse to intensify, we will

almost certainly relapse.

Relapse Prevention

Preventing relapse requires that we

develop a plan that involves diversion activities,

coping skills, and emotional

support. Our decision to cope with

cravings is aided by knowing: (1)

there is a difference between a

lapse and a relapse; and (2)

continued coping with the craving

while maintaining the new behaviour

will eventually reduce the craving.

These coping skills can make the

difference when cravings are

intense:

Ask for help from an

experienced peer and use

relaxation skills to reduce the

intensity of the anxiety associated with

cravings.

Ask for help from an

experienced peer and use

relaxation skills to reduce the

intensity of the anxiety associated with

cravings.

Develop alternative

activities, recognize “red

flags,” avoid situations of

known danger to maintaining new

behaviour, find alternative ways

of dealing with negative emotional states, rehearse

responses to predictably

difficult events, and use stress

management techniques to create

options when the pressure is

intense.

Develop alternative

activities, recognize “red

flags,” avoid situations of

known danger to maintaining new

behaviour, find alternative ways

of dealing with negative emotional states, rehearse

responses to predictably

difficult events, and use stress

management techniques to create

options when the pressure is

intense.

Reward yourself in a way

that does not undermine your

self-caring efforts.

Reward yourself in a way

that does not undermine your

self-caring efforts.

Pay attention to diet and

exercise to improve mood, reduce

mood swings, and provide added

strength to deal with stressful

circumstances and secondary

stress symptoms, including loss

of

sleep, eating or elimination

problems, sexual difficulties,

and breathing irregularities.

Pay attention to diet and

exercise to improve mood, reduce

mood swings, and provide added

strength to deal with stressful

circumstances and secondary

stress symptoms, including loss

of

sleep, eating or elimination

problems, sexual difficulties,

and breathing irregularities.

SOURCES

Our descriptions of various health

models have been pieced together

from a variety of sources. For

further and more detailed

information we can direct you to the

following (non-exhaustive)

list:

Stages of Change model

detailedoverview.htm

http://www.conts.com/Self%20change.htm

The Health Belief Model

http://www.utwente.nl/cw/theorieenoverzicht/theory%20clusters/health%20communication/health_belief_model/

http://www.ohprs.ca/hp101/mod4/module4c3.htm

http://heb.sagepub.com/content/11/1/1

http://midrangeborrowedtheory.weebly.com/critical-elements-health-belief-model.html

The Precede-Proceed Model

http://www.lgreen.net/precede.htm

http://envirocancer.cornell.edu/obesity/intervention101.cfm

http://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-contents/overview/chapter-2-other-models-promoting-community-health-and-development/section-2

The Relapse-Prevention Model

http://www.albertahealthservices.ca/2485.asp

http://www.tgorski.com/gorski_articles/developing_a_relapse_prevention_plan.htm

http://www.recovery.org/topics/relapse-prevention/

http://www.addictionsandrecovery.org/relapse-prevention.htm

http://psychcentral.com/lib/relapse-prevention/000273

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3163190/

![]() Ask for help from an

experienced peer and use

relaxation skills to reduce the

intensity of the anxiety associated with

cravings.

Ask for help from an

experienced peer and use

relaxation skills to reduce the

intensity of the anxiety associated with

cravings.

![]() Develop alternative

activities, recognize “red

flags,” avoid situations of

known danger to maintaining new

behaviour, find alternative ways

of dealing with negative emotional states, rehearse

responses to predictably

difficult events, and use stress

management techniques to create

options when the pressure is

intense.

Develop alternative

activities, recognize “red

flags,” avoid situations of

known danger to maintaining new

behaviour, find alternative ways

of dealing with negative emotional states, rehearse

responses to predictably

difficult events, and use stress

management techniques to create

options when the pressure is

intense. ![]() Reward yourself in a way

that does not undermine your

self-caring efforts.

Reward yourself in a way

that does not undermine your

self-caring efforts. ![]() Pay attention to diet and

exercise to improve mood, reduce

mood swings, and provide added

strength to deal with stressful

circumstances and secondary

stress symptoms, including loss

of

sleep, eating or elimination

problems, sexual difficulties,

and breathing irregularities.

Pay attention to diet and

exercise to improve mood, reduce

mood swings, and provide added

strength to deal with stressful

circumstances and secondary

stress symptoms, including loss

of

sleep, eating or elimination

problems, sexual difficulties,

and breathing irregularities.