As growth picks up around the developing world, and the long-predicted convergence between rich and poor countries appears to be occurring, ideas of exploitation are akin to conspiracy theories in some quarters, and debate has tended towards how poor countries can internalise and promote liberalisation policies, mitigating their most pernicious aspects where possible. But this may be more apparent than real; dependency may have shifted from its original concept to a more pernicious form.

Hitherto, wealthy countries were able to plunder their colonies for material benefits, such as raw materials like rubber, sugar, and slave labour. Today, poor countries have taken enormous loans from wealthy countries in order to stay afloat. Paying off the compound interest from this debt prevents them from investing resources into their own country.

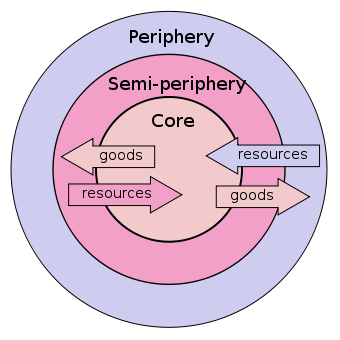

The financial crisis that began in 2007, and still apparently continues, has highlighted the role of global financial markets in creating what may be described as new dependency relationships. Old dependency theory was a structural-Marxist theory. It hypothesised that the world capitalist economy is structurally arranged to facilitate massive transfers of capital from developing countries to the developed world. The new dependency theory agrees that net outflows of capital from developing countries have been continuing unabated for the past three decades. But—and this is a key difference between new and old dependency theory—these illicit flows are a problem not only for developing countries but also for developed ones.

This is so for two reasons. First, the net flow of capital is not necessarily transferred to or invested in the developed world. Rather, the transfer of financial resources from developing countries joins a large pool of capital registered in offshore locations. Second, there is evidence that developed countries are subject to net external outflow of capital as well. In contrast to old dependency theory, the new theory suggests that capital transfers do not necessarily operate on a regional or intra-national basis; rather, wholesale global financial markets have emerged as gigantic re-distributive machines that play a key role in the continuing and growing gap between rich and poor world-wide.

Brazil is an example of a nation with a rapidly growing economy that is nonetheless still sullied by dependency on foreign nations. Long colonized by the Portuguese, Brazil continues to export most of its raw materials and agricultural production while many Brazilians continue to live in poverty and are malnourished.

"Latin America is today, and has been since the sixteenth century, part of an international system dominated by the now-developed nations.... Latin underdevelopment is the outcome of a particular series of relationships to the international system." [Susanne Bodenheimer]

And, having now introduced the situation in South America, this is an appropriate moment to describe a magnificent work on development, with particular relevance to the area. This is Open Veins of Latin America, by Eduardo Galeano with a foreword by Isabel Allende.

Ms Alllende famously took a copy with her when she fled Chile after the 1973 coup, and Hugo Chávez (1954-2013). ex-President of Venezuela, gave one to Barack Obama when they met at a summit 36 years later.

Hopefully Obama read it. It is possibly the most lucid account of dependency theory there is, combining rhetoric, poetry, statistics and history in a unique way.

As with most Marxist-inspired tirades, it is not a complete analysis of Latin America's history – it probably exaggerates the villainy of capital and heroism of peasants. But it presents a perspective on the truth that any serious development worker or academic should have intellectual access to. This is as relevant today as ever. It is critical that voters in the rich world learn that their wealth is related to a historic exploitation of other parts of the world, especially when they are eventually asked to readjust their living habits and conditions in order to better accommodate the just requirements of poorer countries.

In the foreword Isabel Allende wrote "Latin America is the region of open veins.

"The division of labour among nations is that some specialize in winning and others in losing. Our part of the world, known today as Latin America, was precocious: it has specialized in losing ever since those remote times when Renaissance Europeans ventured across the ocean and buried their teeth in the throats of the Indian civilizations. Centuries passed, and Latin America perfected its role. We are no longer in the era of marvels when face surpassed fable and imagination was shamed by the trophies of conquest— the lodes of gold, the mountains of silver. But our region still works as a menial. It continues to exist at the service of others' needs, as a source and reserve of oil and iron, of copper and meat, of fruit and coffee, the raw materials and foods destined for rich countries which profit more from consuming them than Latin America does from producing them.

"Back in 1913, President Woodrow Wilson observed: "You hear of ‘concessions' to foreign capitalists in Latin America. You do nor hear of concessions to foreign capitalists in the United States. They are not granted concessions." He was confident; "States that are obliged ... to grant concessions are in this condition, that foreign interests are apt to dominate their domestic affairs. . . . ," he said, and he was right."

AMERICA AND NEO-DEPENDENCY THEORY

When I planned this article, it was my intention - based on my belief at that time - to point out how neo-dependency theory was being demonstrated and supported by the United States' policy and activity in Latin America, and China's behaviour similarly in Africa.

Subsequent developments and my own consequent research has turned that belief on its head.

American influence and its policy towards Latin America and - even more pointedly - the Latin American countries' relationship with the United States as opposed to that of China, has modified China's major international sphere of influence. In addition to Africa, which has increasingly engaged with China--politically, socially and economically, has now been added involvement with Latin America, necessitating a total re-think by the United States of its own policy.

CHINA AND NEO-DEPENDENCY THEORY

African states and China are very connected via the Forum On China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC)(2), an official forum between the People's Republic of China and the states in Africa. There have been five summits held to date, with the most recent meeting having occurred from July 19-20, 2012 in Beijing. Previous summits were held in October 2000 in Beijing, December 2003 in Addis Ababa, November 2006 in Beijing, and November 2009 Sharm-El-Sheikh, Egypt.

A dissertation by the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, "asserts that Africans are willing partners of the Chinese, motivated by their state-centric belief that engagement with China is in their national interest. This assertion contradicts the assumption of most literature to date that appears to borrow from the logic of dependency theory and presents African nations as pawns, subject to the demands of a dominant and exploitative China, who is benefiting at Africa’s expense." (5)

"Economic trends from the decade before the launch of the FOCAC and the 10 years following indicate that increasing engagement with China has not been detrimental to African economic development. Following the establishment of the FOCAC in 2002, Africa as a region is reporting significantly higher GDP growth rates, increased GNI, and GDP per capita. Additionally, African states and China have on the whole experienced a balanced trade flow with few exceptions of uneven balances not always in favor of China. Clearly African states are benefiting from their relationship with China. A case study of Nigeria in 2011 revealed that Nigerians are willing to experience a continued trade deficit with China in order to achieve other important objectives. Nigerians are looking to learn from China’s industrialization process and the economic policies that have resulted in higher growth rates and amelioration of poverty. Chinese investments in Nigerian and African infrastructure development are considered significant and relevant for economic and social development. The influx of affordable Chinese goods has increased the spending power of the average Nigerian and increased the profit margins for Nigerian retailers. Nigerians are engaging with China because it is in their best interest and as this relationship continues to grow, it will need to be managed in order to maximize the benefit to Nigeria." (ibid)